The Wednesday of 23 August 1939 marks an extraordinarily important date in the history of Central Europe, indeed all of Europe.

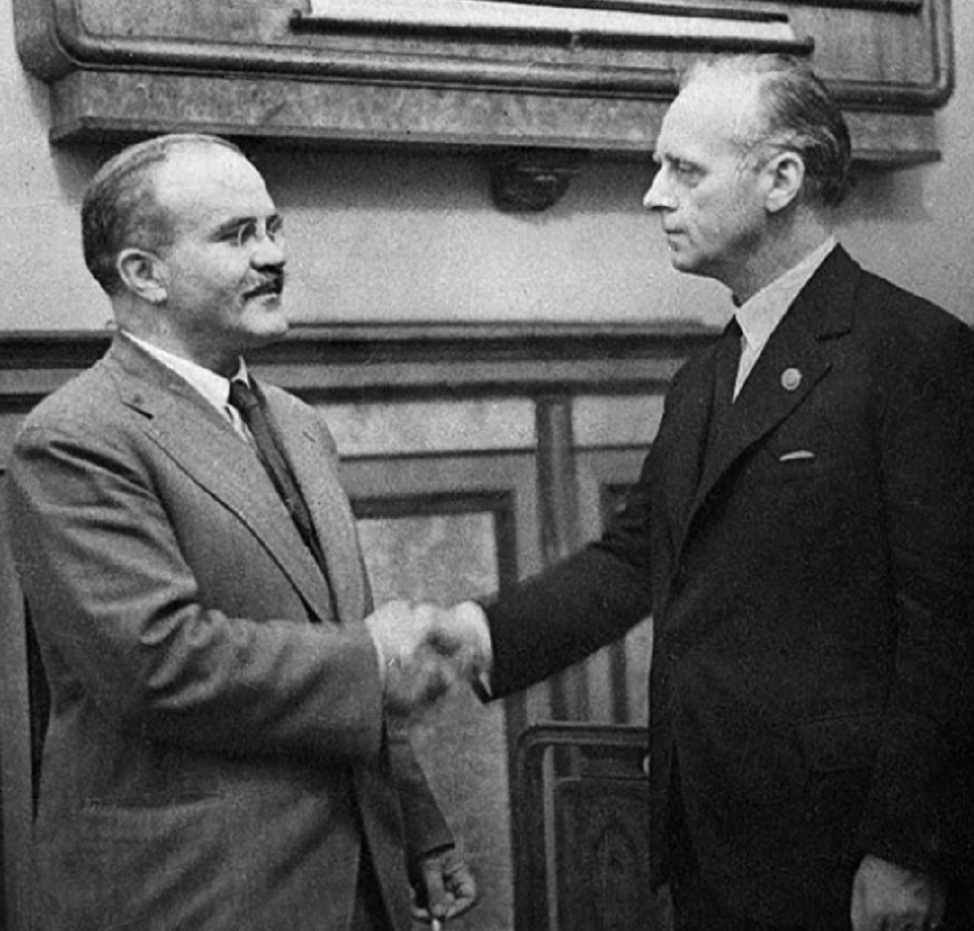

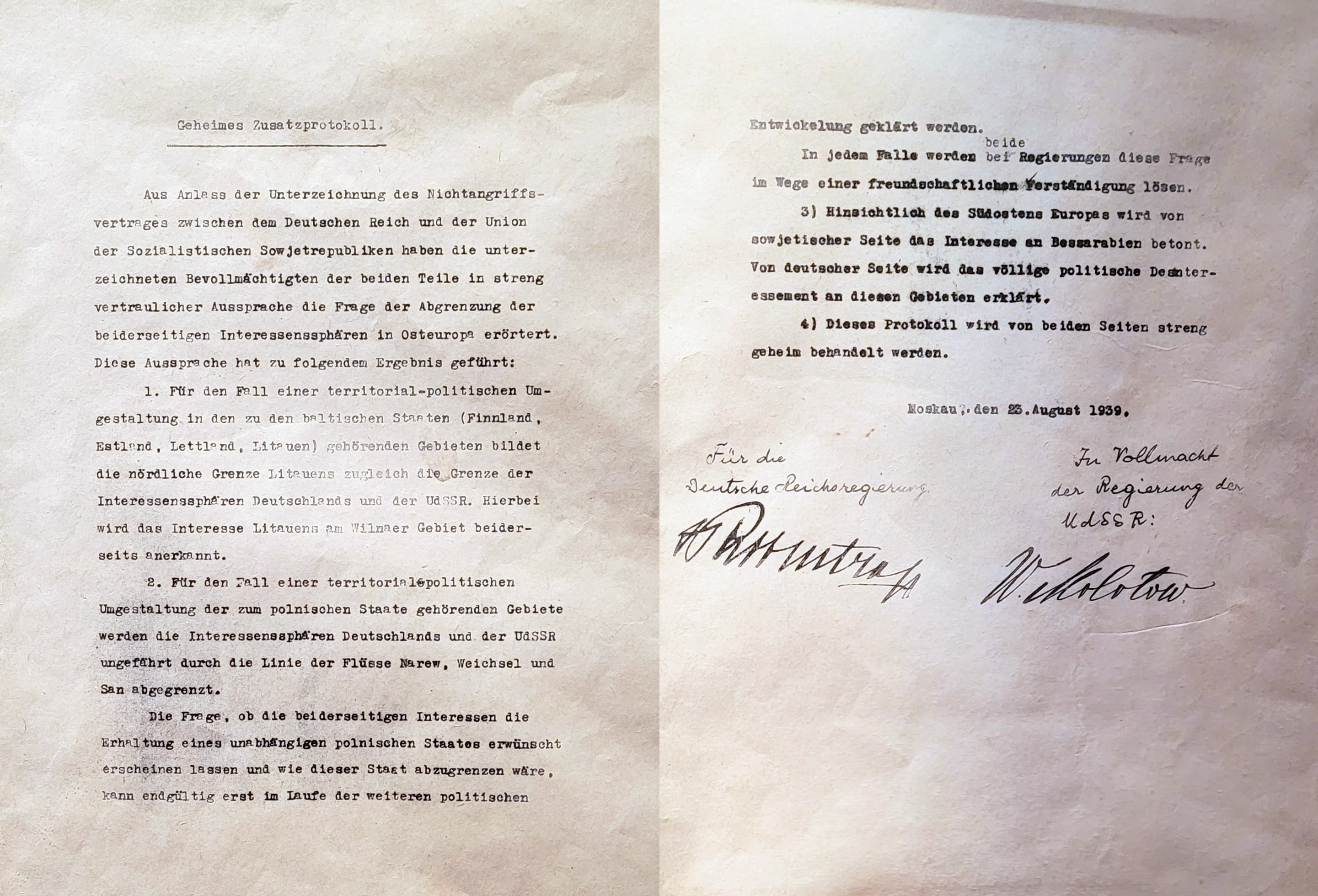

On that day, Joachim von Ribbentrop, foreign minister under the German Reich, flew to Moscow and, after brief negotiations with Vyacheslav Molotov, Soviet foreign commissioner, signed – in the presence of Joseph Stalin himself – the non-aggression agreement between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, soon to be known as the Molotov–Ribbentrop (or the Hitler–Stalin) Pact.The most important part of that document, with a direct impact on the developments in Europe in the following days and weeks, was the secret additional protocol, which divided Central and Eastern Europe into German and Soviet spheres of influence. The former was to include the western half of Poland and Lithuania (soon to be handed over to Moscow), while the latter the eastern half of Poland, Finland, Estonia and Latvia, as well as Romanian Bessarabia.

Hitler feared a war on two fronts, and at the same time insisted the arrangements be made quickly because of the imminent arrival of the autumn rains and fog, which could stop the Blitzkrieg (German: Lightning War), making it much easier for the Poles to defend themselves. In order to achieve his aims, he had to secure at least the neutrality – and preferably active cooperation – of the Soviets during the attack on Poland and the subsequent showdown with the West. This was the reason why the German side willingly and speedily agreed to such a vast expansion of the Soviet sphere of influence and in practice the borders of the USSR. Looking at the scene from a different perspective, one can see that without Stalin’s agreement and cooperation with Hitler, who ‘just a while ago’ was the number one enemy for the communists, the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 would almost certainly not have occurred, and any additional months of peace might have changed the fate of the world.

Germany and the Soviet Union did not give Europe and the world that chance, however. On 1 September 1939, Germany attacked Poland, soon followed by the USSR, which did the same on 17 September. In the areas occupied by the Wehrmacht and the Soviet army, war crimes were committed from the very first days of the onslaught. Soon deportations of Poles to concentration and forced labour camps and the Soviet Gulag incarceration facilities began. The repressions were aimed at the broadly defined leadership and opinion-forming class. In the spring of 1940 during the Katyn Massacre, the Soviets murdered more than 20,000 Polish prisoners of war. On 30 November 1939 the Soviet Union invaded Finland, which – thanks to a fierce defence – managed to save its independence. In the autumn of 1939, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia had to conclude friendship agreements with the USSR and allow the Soviet army into their territory. After less than a year, at the beginning of August 1940, all three were incorporated into the USSR. In June 1940 the Soviets, threatening to invade the country, forced Romania to hand over Bessarabia and the northern half of Bukovina. Cruel repressions took place in the Baltic states occupied by the USSR, especially the deportation of hundreds of thousands of men, women and children to Siberia. The Finns and Romanians had to take in hundreds of thousands of refugees fleeing the areas annexed by the Soviets, and those who remained were exposed to Soviet repression. At the same time, the Germans had already murdered a significant part of the Polish intelligentsia, established the Auschwitz concentration camp and set up ghettos for Jews.

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact concluded on 23 August Pandora’s box. On that day the worst plagues prepared by the totalitarian systems – Nazism and Stalinist communism – were inflicted on Europe. The choice of 23 August as the European Day of Remembrance for Victims of Totalitarian Regimes is therefore fully justified.