We remember little, increasingly little, of 20th-century history. Generally only as much as the most powerful media of memory record for a while in the collective imagination: the most repeated themes of major films, symbols inscribed in school textbooks and mainstream museum practices.

At the same time, a wave of protests continues to rise for the introduction into the ‘catalogue of compulsory memory’ of the forgotten, wronged and humiliated victims whom we have not previously remembered or only pretended not to notice. What criterion should be adopted in this competition for the ever-shrinking tiny piece of public attention, of collective memory? Maybe it is worth remembering those victims who seem to be the most forgotten, who have not left communities of mourners, who have been completely ‘trampled into the ground’ (sometimes quite literally) who have not had any system of cultural symbols created around their suffering?Let me give one example. I wonder how many history books in the world, how many films, how many museums focusing on 20th-century history mention a single order, preserved in writing and already available to professional researchers for years, on the basis of which 111,091 people were executed? There are few such crimes, even in the bloody history of the 20th century. This one, in fact, was five times larger in scale than the Katyn operation, certainly better known and commemorated, but which claimed the lives of ‘only’ some 22,000 Polish officers and prisoners of war on the basis of Stalin’s decision of March 1940.

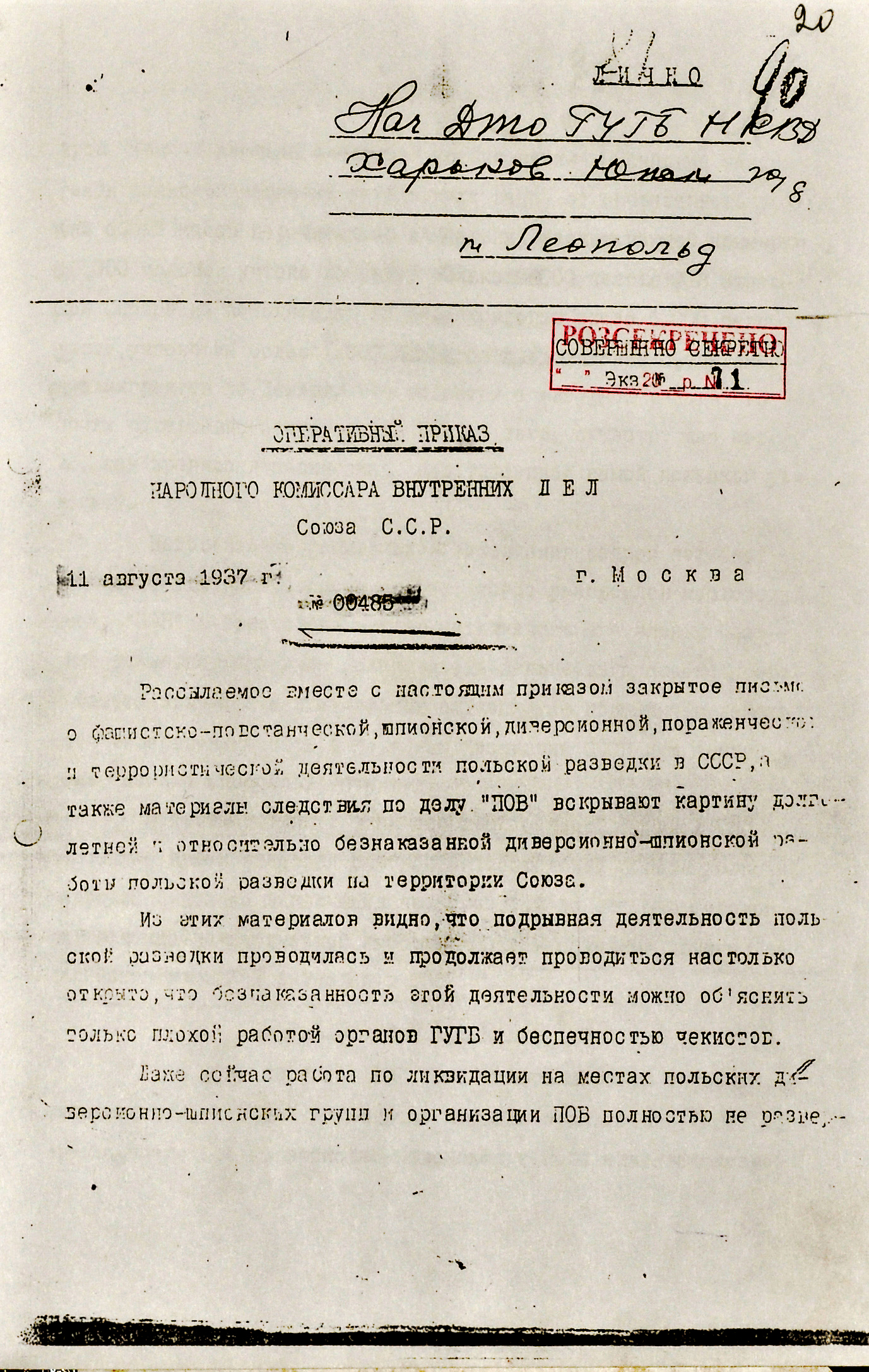

The order whose victims I take the liberty of reminding you of here was issued in the same political circle, only three years earlier, even before the outbreak of the Second World War. It was order no. 00485 of 11 August 1937 issued by the head of the NKVD, Nikolai Yezhov, on the basis of a decision two days earlier by the Politburo of the All-Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks). It was an order for the genocide of the Polish minority living in the USSR at the time. There was probably no single document before that entailed the deliberate liquidation of such a large number of people on the basis of ethnicity. Yezhov proclaimed the fight against the ‘fascist-insurgent, spying, sabotage, defeatist and terrorist activities of Polish intelligence in the USSR’. He also set a clear task for subordinate NKVD services throughout the country: a ‘complete liquidation of the hitherto untouched broad, diversionary and insurgent backup resources’ and the ‘basic human reserves’ of Polish intelligence in the USSR’.

Such ‘backup resources’ and ‘basic reserves’ could be formed by anyone who had Polish nationality entered in their passports. According to the 1926 census in the USSR, there were 782,000 such people. According to the following census (1939), the number of Poles in the USSR decreased to 626,000. This was precisely the effect of the system of unprecedented persecution to which Poles were subjected in the Stalinist state. More than 150,000 of those who were shot dead (not just in 1937–38) died during deportations or starved to death in 1932–33. At least every second adult male was deprived of life in this Polish community of fate.

Groundbreaking in understanding the scale of this operation was the work of Russian researchers from the Memorial Nikita Petrov and Arseniy Roginsky (1993 and 1997, respectively), who presented official internal NKVD reporting. These are its figures: in the Polish operation, 143,810 people were arrested between September 1937 and September 1938. Of these, 111,091 were executed. Not all of them were ethnic Poles, whose number among those slaughtered in this one operation is estimated between 85,000 to 95,000. However, Poles were systematically killed in the Soviet state in other operations as well: they were the victims of the anti-kulak operation of 1930–31, the Great Famine of 1932–33 both in Ukraine and Kazakhstan (after all, it was not only Ukrainians and not only Kazakhs who died from starvation), and as a result of successive waves of arrests and deportations of the Polish population first from the border areas with the Second Polish Republic in Soviet Ukraine and Belarus, and then in 1936 from these republics to Kazakhstan in general. At the height of the terror (1937–38), Poles were also shot en masse as part of smaller NKVD schemes, such as the German operation (liquidating ‘German spies’), the ‘cleansing’ of the NKVD itself from the Polish element still introduced to it in large numbers by a Bolshevik revolutionary and politician Felix Dzerzhinsky, and many others.

The validity of order no. 00485, originally intended to be in force for three months, was extended to nearly two years. Its deadly effects were completed four days later by another order issued by Yezhov. It was numbered 00486, and concerned the families of ‘traitors to the fatherland’ (not just Poles). Only those who had betrayed their loved ones could avoid arrest. Children over the age of 15 were subject to ‘adult’ repression. Younger ones were to be sent to orphanages or to work.

The exceptional scale of repression directed by the Soviet state against Poles has been pointed out by Harvard University professor Terry Martin. On the basis of a named list of victims shot in Leningrad in the period 1937–38, he calculated that Poles were killed 31 times more often than their number in the city would suggest. In other words, a Pole in and around Leningrad was 31 times less likely to survive during the height of the Great Terror than the average resident of the city most affected by Stalin’s crimes. Yale University professor Timothy Snyder calculated the following numbers for the entire Soviet Union at the time of the Great Terror: the Poles were, unfortunately, a chosen people in it. Stalin’s choice determined that they were 40 times more likely to be shot than the average for all nations of the USSR. Poles accounted for 0.4 per cent of the total population in the USSR, while they made up around 13–14 per cent of the victims in the 681,000 executed between 1937 and 1938. So much for dry statistics based on NKVD data. But, as Snyder rightly wrote in his monograph Bloodlands (2010), we must above all remember that each victim had a name, each has an individual biography and each deserves human remembrance. With poignant empathy, the fate of Poles murdered as part of NKVD operations in Ukraine in 1937–38 was portrayed by perhaps the most eminent contemporary scholar of the Stalinist system, Professor Hiroaki Kuromiya of Indiana University. In his book The Voices of the Dead (American edition 2007), we can see this great crime through the prism of the individual fates of people executed simply for saying ‘Poland is a good country’ (this was interpreted as ‘fascist agitation’), or for refusing to renounce a Polish husband or wife.

The memory of this crime must be claimed in the name of historical truth about the times of the Great Terror. This concept, linked to the years 1937–38, present in all history textbooks (including Polish ones) of the 20th century, is most often limited to Stalin’s crackdown on the old Leninist cadres and the Red Army’s top brass. Today’s historical propaganda in Russia, uncritically adopted by the dominant part of the media in Poland, presents the Great Terror, or the Great Purge, as an internal tragedy of the Russians, a ‘domestic conflict’ that only Russians have the right to talk about. Meanwhile, according to NKVD data, of the 681,000 people executed between 1937 and 1938, 247,000 were victims of ‘nationality operations’ (led by the Polish), and more than 350,000 were kulaks (not necessarily Russians; there were also a great many Poles among them, but certainly no communists in this category). The Polish victims, so numerous in this terrible crime, remain silent. We cannot give them a voice, but we can, and we must, restore their memory. We cannot allow them to be dissolved in the false image of the Great Purge, in which only Bukharin, Kamenev, Zinoviev or Tukhachevsky are remembered.

There are not any graves left behind for the victims of the ‘Polish operation’. There was no Anna Akhmatova to mourn them in her Requiem, nor Arthur Koestler to show their fate in Darkness at Noon. These were ordinary people, not generals, not renowned poets or worldfamous political activists. They were killed and their families deported deep into the Soviet Union, condemned to oblivion alone. They did not leave influential friends to claim their memory. Then came the Second World War and its great tragedies. There was no room left for the memory of the victims murdered before that war to be cultivated by its later victors.

Yet it is precisely for this reason that once we know about them, we should not forget them. It is for the same reason that we should not forget the great sacrifice of the Jewish genocide committed by German Nazism. We must remember the victims of the crime all the more strongly: the more they seem forgotten, nameless, powerless – this is what humanity, our humanity, demands of us. Would it not be worthwhile to become aware of the existence of these people, each of whom had a name, each of whom had a face, but each of whom became Homo sacer (a person made worthless and located outside the law) – exactly as Giorgio Agamben depicted it on the basis of the Holocaust experience described by Primo Levi. Perhaps it is worth showing, also to today’s world, this example of a great crime that transforms people into victims – killed with impunity but not sacrificed – into ones excluded from the bios, simply because they belonged to a group chosen by political power to be shot dead.