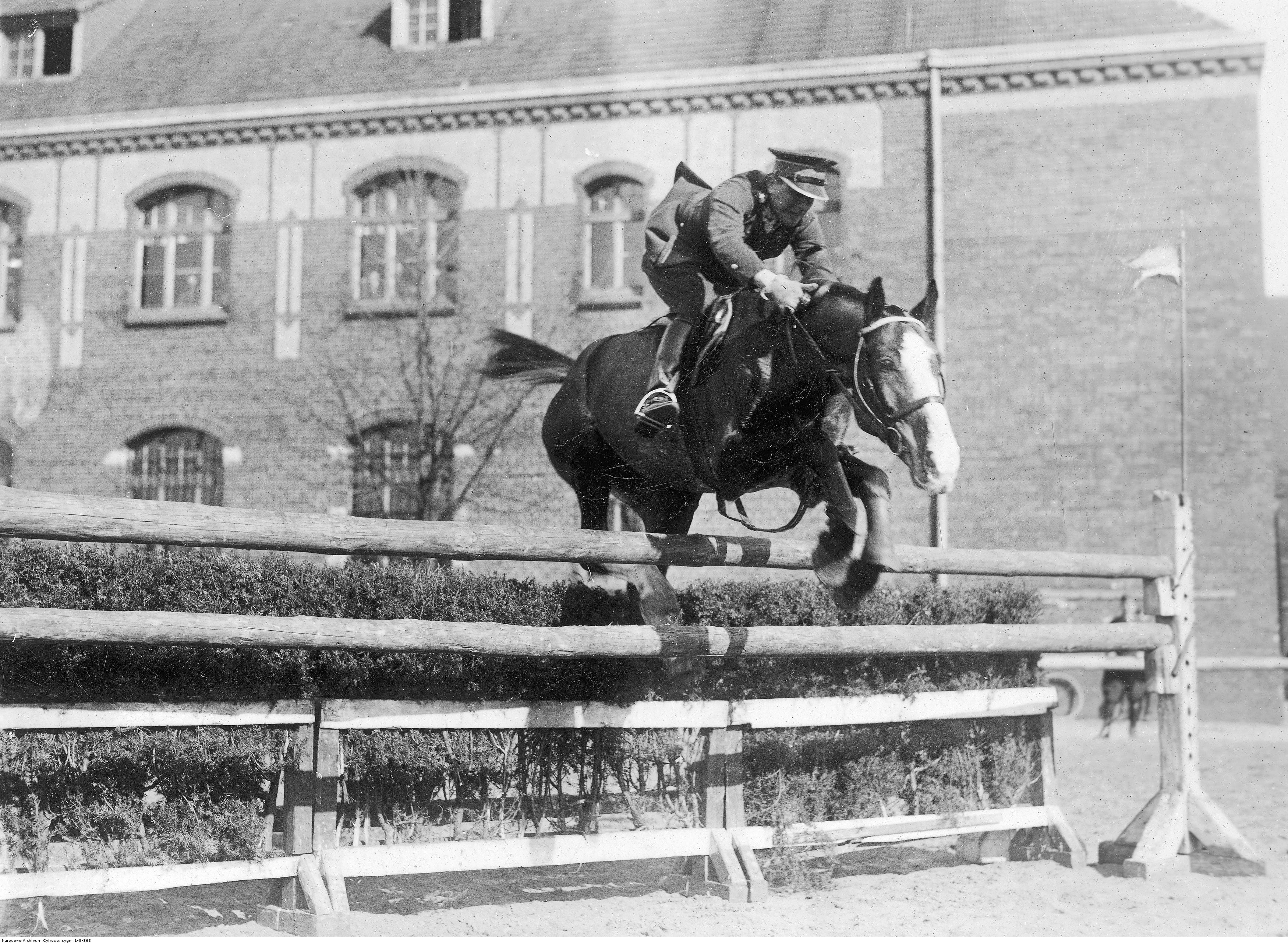

On 27 July 1924, at the VIII Summer Olympics in Paris, the Polish track cycling team, Józef Lange, Jan Lazarski, Tomasz Stankiewicz and Franciszek Szymczyk, triumphantly won a silver medal. On the same day, Adam Królikiewicz, riding Picador, clinched the bronze in show jumping. These victories marked Poland’s first Olympic medals. Commemorating the 100th anniversary of this momentous achievement, the Sejm has declared 2024 the Year of Polish Olympians. However, the stories of Polish Olympic athletes throughout the 20th century encompass not only glory but also enslavement and resistance against oppressive regimes.

A new reality

The outbreak of the Second World War abruptly halted the athletes’ preparations for future Olympic Games, cutting short the promising momentum achieved in Paris. Having only joined the Olympic arena in 1924, Poland had already amassed a considerable tally of medals, participating in eight Olympic Games (four summer and four winter) between the wars.

According to research undertaken by Ryszard Wryk, one of the foremost sports historians, a total of 327 Polish athletes competed in the Olympics during the Second Republic: 266 in the summer and 61 in the winter Olympics. Among them were 307 men and only 20 women. On the eve of the outbreak of the Second World War, most of the men were mobilised for the army and many of the women were involved in caring for the sick and wounded. Following the capitulation to Germany on 6 October 1939, they shared the fate of thousands of Polish prisoners of war who were captured and confined in prisoner-of-war (POW) camps.

Thirty-four Polish Olympians were taken prisoner by the Germans, 29 were sent to POW camps after the September defeat and five more after the capitulation of the Warsaw Uprising, including its commander General Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski, an equestrian, cavalryman and a member of the national team at the 1924 Olympics in Paris; 26 were imprisoned in oflags (prison camps for captured enemy officers) and eight in stalags (prison camps for non-commissioned officers and privates). Despite their imprisonment, these athletes endeavoured to recreate the spirit of not only Polish sports but also the global sports movement, including the Olympic ideals initiated by the French educator Pierre de Coubertin. Coubertin’s vision of Olympism as ‘a philosophy of life, which expresses and unites the values of body, will, and spirit in a balanced whole’, sought to inspire peaceful competition among nations. Although this vision had been shattered by recent events, it provided a sense of purpose and resilience for those who had left the Olympic stadiums for the harsh realities of camp life.

Captive sport

The rules for the treatment of prisoners of an enemy state, from their capture to their release, were governed by the Geneva Convention of Prisoners of War, 27 July 1929, of which Germany was one of the signatories. This convention obliged states holding prisoners of war to treat them humanely, to provide them with decent living conditions and to allow them to pursue cultural, scientific, educational and sporting activities.

The organisation of sporting life was regulated by Article 17 of the Convention of Prisoners of War, which stated that the detaining authorities ‘shall encourage, as far as possible, intellectual and sporting entertainment organised by prisoners of war’. The rules for the organisation of sport in POW camps were regulated by the ordinances of the German camp authorities and their superiors in Berlin.

Sport within the camps took on an institutionalised form, becoming a crucial part of the daily routine for maintaining physical wellbeing and mental equilibrium. Morning gymnastics and short marches were mainly obligatory, while sports competitions were conducted by special organisational units adhering to strict regulations. These competitions ranged from establishing camp champions in various sports to friendly tournaments and show contests – physical fitness tests were particularly popular.

The POW Olympic Games of 1940 and 1944 held profound symbolic significance. The first of these games took place from August 31 to 8 September 1940, at Stalag XIII Langwasser near Nuremberg, initiated by Platoon Sergeant Jerzy Słomczyński, a physical education instructor. Polish, French, Belgian, Dutch, Yugoslavian and British prisoners of war participated in these games. In 1944, the POW Olympics were held at Oflag II D Gross-Born and Oflag II C Woldenberg, observing full Olympic ceremonial traditions. These events transcended mere sporting competitions; they became political demonstrations, asserting that the universal Olympic spirit endured despite the ravages of war. As sports historian Kazimierz Rudzki eloquently recalled in his 1945 memoirs:

‘This bizarre 1944 Olympics at Woldenberg was more than just a sporting event. It was a symbol of faith in the value and meaning of the Olympic idea, in spite of everything and in spite of everything that happened beyond the reach of the barbed wire.’

Participation in sports was understandably limited to a few well-nourished prisoners. However, even on a small scale, these activities fostered a sense of community and solidarity among the POWs. Sporting events provided a crucial means of integration, offering a semblance of normalcy and hope in an otherwise harsh and oppressive environment.

Guarding against ‘barbed-wire fever’

Determining the extent of physical activity in POW camps is challenging, as prisoners in stalags were subjected to hard labour and harsh living conditions far worse than those in oflags. The Germans frequently violated the Geneva Convention, making physical exercise difficult and often banning it outright. Despite the constant threats to their health and lives, some prisoners, even in the stalags, managed to engage in physical activities with the tacit approval or collusion of camp authorities. These activities helped them stay fit, combat the mental toll of confinement and provided a semblance of a ‘normal’ life.

Even in isolation, many imprisoned Olympians sought to maintain their physical activity and encouraged it among their fellow prisoners. Notable figures include Zygmunt Weiss (1903–1977) and Henryk Niezabitowski (1896–1976), both of whom defended Warsaw and were subsequently imprisoned in Oflag IV A Hohnstein near Dresden. Weiss, an athlete, sprinter and twice an Olympian (1924 and 1928), moved into sports journalism, specialising in cycling. Niezabitowski, a rower and ice hockey player, became a key promoter of sports in the camp, particularly from the spring of 1941.

Another dedicated figure was Tadeusz ‘Ralf’ Adamowski (1901–1994), a talented all rounder and an ice hockey player, a member of the national team at the 1928 Olympics. He was sent to Oflag II C Woldenberg in May 1940. He was a member of the Military Sports Club (WKS) ‘Orla’, where he played basketball and was an organiser and active participant in sports competitions under the name ‘Olympic Year in Camp II C’.

One of the most active promoters of a culture of physical activities in the camp was Jan Baran-Bilewski (1895–1981), an athlete and pentathlete. Captured during the September Campaign, he was first imprisoned in Oflag II B Arnswalde. Despite the unstable situation, taking advantage of his own sporting background and the relatively good conditions for physical activity, he became involved in popularising physical exercise. He was the chief organiser of the three-day sports competition held on 29–31 August 1940, which some historians consider to be the first POW Olympic initiative.

Numerous Olympians contributed significantly to promoting physical education in the camps, including Jerzy Gregołajtis (1911–1978), hockey player and Olympic basketball player; Franciszek Kawa (1901–1985), Olympic athlete; Adam Kowalski (1912–1971), hockey player; Klemens Langowski (1911–1944), Olympic sailor; and Kazimierz Laskowski (1899–1961), fencing champion and pioneer of boxing in Poland, who held regular gymnastics, including specific groups of prisoners, popularised physical culture and participated in the work of the Association of Military Sports Clubs. K. Laskowski conducted seven self-defence and hand-to-hand combat courses, in which he trained more than 200 prisoners of war. The following athletes, despite their imprisonment, dedicated themselves to the promotion of physical activity: Witalis Ludwiczak (1910–1988), Olympic hockey player; Stanisław Sośnicki (1896–1962), athlete; Kazimierz Szempliński (1899–1971), sword champion; Janusz Ślązak (1907–1985), rower and ensign of the Polish Olympic team; and Wojciech Trojanowski (1904–1988), Olympic athlete. They organised lectures, daily gymnastics, sports clubs and competitions, instilling a sense of unity and resilience among their fellow prisoners.

Among the chief promoters of physical education and camp sport were undoubtedly Wacław Gąssowski (1917–1959), six-times Polish champion in athletics; Janusz Komorowski (1905–1993), one of the best Polish equestrians of the younger generation; Seweryn Kulesza (1900–1983), Olympic medallist in equestrian; prize-winning boxer Walter Majchrzycki (1909–1993); Olympic basketball player Zenon Różycki (1913–1992); shooter Jan Suchorzewski (1895–1965); and one of the Poland’s best sabre players Marian Suski (1905–1993) – all of them were actively involved in various forms of mainstream sport. These individuals, through their unrelenting efforts, provided not only physical sustenance but also a psychological lifeline, reminding their comrades of the world beyond the barbed wire and the enduring spirit of the Olympics.

In the shadow of conspiracy

The Second World War tested the patriotism of Polish Olympic athletes as never before. Most faced this trial with dignity and courage, with some making the ultimate sacrifice of their lives. Others struggled merely to survive, while a few, often under extreme duress, collaborated with German or Soviet occupiers. Before the war, six Olympians had already died, and the fates of seven others remain unknown. Of the 275 athletes alive on 1 September 1939, 51 were born before 1900, making them about 40 or older when the war began. The largest group, 138 athletes, were in their thirties, born between 1900 and 1910, while 56 were in their twenties. These ages made them eligible for mobilisation in either active or auxiliary military service.

In the summer of 1939, 106 former Olympians were mobilised into the Polish army. Among them, five were killed and two disappeared without a trace. The most prominent among those killed during the September Campaign was athlete Antoni Cejzik (1900–1939), who died near Zaborowo in early September 1939. Eighteen Olympians found themselves in POW camps. Nine Polish officer athletes, policemen and civil servants were captured by the Soviets, deported to camps in Kozielsk or Starobielsk, and later shot in Katyn, Kharkiv or Moscow’s Lubianka.

Some athletes undertook missions beyond direct combat. Olympian Halina Konopacka (1900–1989) assisted her husband Ignacy Matuszewski in the evacuation of 75 tonnes of Bank of Poland gold to France via Romania, Turkey and Syria in September 1939. Twenty-eight Olympic athletes engaged in conspiratorial activities in occupied Poland, involving military, intelligence, sabotage and sport within the Union of Armed Struggle, later transformed into the Home Army, or smaller resistance groups.

Among the most notable was athlete Janusz Kusociński (1907–1940), who fought in the September Campaign and was wounded twice. During the occupation’s early months, he worked as a waiter at the ‘Pod kogutem’ bar in Warsaw, known as the Sportsmen’s Inn, as its staff were predominantly pre-war athletes. Simultaneously, he joined the underground, active in the Wilki (Wolves) Military Organisation and distributed illegal press. Arrested by the Gestapo, Kusociński was imprisoned in Pawiak, taken to Palmiry near Warsaw, and executed on 21 June 1940.

Skier and glider pilot Bronisław Czech (1908–1944), arrested for his role as a Tatra courier, escorting people and parcels from occupied Poland to Hungary, died in a concentration camp in 1944. Stanisław Marusarz (1913–1993), another courier, made a daring escape by jumping from the window of Kraków’s Montelupich Prison in 1940, twice evading execution. After the German invasion of Hungary, he continued his resistance efforts under an alias, training Hungarian ski jumpers. The story of Olympic boxer Antoni Czortek (1915–2004), a prisoner in Auschwitz from 1943 to January 1945, is equally harrowing. Forced to fight an SS guard face-to-face for his survival, Czortek’s courage was emblematic of the resilience shown by many Olympians. Wrestler Ryszard Błażyca (1896–1981), refusing to train German club fighters, was sent to an forced labour camp in a remote part of Germany.

The clandestine sports activities were a unique form of resistance against the occupiers and included illegal football matches, competitions and training sessions organised in POW camps. Fifteen Polish Olympians were involved in these efforts, including football legend Henryk Martyna (1907–1984); footballer and doctor Stanisław Cikowski (1899–1959); rower and hockey player Henryk Niezabitowski; and fencer Kazimierz Laskowski (1899–1961), who organized boxing competitions and hand-to-hand combat training in the oflag.

A (un)better world

Amid the turmoil of war, 41 Polish Olympic athletes adopted a stance of passive survival, striving to endure and provide for their families under dire circumstances. Cross-country skier Franciszek Bujak (1896–1975) found work in a ski factory in Zakopane, while footballer Wawrzyniec Cyl (1900–1974) toiled in a car repair shop in Łódź. Athlete Julian Łukaszewicz (1904–1982) worked at the Łódź power station and Stefan Ołdak (1904–1969) took on the role of a athletics judge. Rower Roger Verey (1912–2000), mobilised but unable to locate his unit, spent weeks in September 1939 searching for it, ultimately surviving the occupation in Krakow by driving trams.

Not all stories ended in survival. Former cyclist Tomasz Stankiewicz (1902–1940), who worked in the automotive and trade sectors, was arrested by chance in 1940, imprisoned in Pawiak and executed in Palmiry. Canoeist Marian Kozłowski (1915–1943), employed as a manual worker in Poznań, was deported to a forced labour camp in a remote part of Germany, where he perished in an Allied bombing raid in 1943. For some athletes, little is known beyond their place of residence during the war. Seven competitors had been living abroad for years, with their exact fates remaining unknown. Boxer Adam Świtek (1901–1960) had resided in France since 1930 and skater Leon Jucewicz (1902–1983) in Brazil since 1928. Karol Szenajch (1907–2001) was aboard a ship returning to Poland from New York when the war broke out.

Among the heroic Olympians were those whose wartime actions were minimal or whose fates are difficult to trace. Yet, a small group made significant concessions to the Soviet or German occupiers, often not by choice but under duress. Their collaboration, whether political, military or through participation in sports competitions organised by the occupiers, reflects the complex and painful choices faced in an (un)better world.

Loud and silent heroes

During the Second World War, 45 Polish Olympic athletes met their tragic end under various circumstances. The post-war fates of the survivors were as diverse as they were poignant. For 41 individuals, little more is known beyond their last known residences. Thirty-two athletes continued their involvement in sport after the war, with ten competing in the 1948 or 1952 Olympic Games. Ninety changed into roles as referees or coaches, either immediately following the war or after concluding their athletic careers. Forty-six distanced themselves from competitive sports entirely, five ended up in Polish prisons or Soviet camps and two were sidelined from their professions for political reasons. Forty-three chose to remain abroad or emigrated.

These athletes’ lives formed a melancholic bridge between the war years and the inception of the new communist regime in Poland. Many pre-war sporting elites found it impossible to accept the new order, prompting some to move their families and professional lives abroad. Yet, a total of 168 pre-war Olympians chose to stay or return to their homeland, where they eventually died.

One such tragic figure was Stanisław Kłosowicz (1906–1955), a leading Polish road cyclist of the interwar period. During the occupation, he lived in Radom, working as a turner. In 1941 he was forcibly taken on a German ‘excursion’ to Katyn, witnessing the Katyn massacre. Arrested by the Soviets in 1945, he was deported deep into the USSR. By the time he returned to Poland in the early 1950s, he was gravely ill and died in 1955. Similarly, Franciszek Koprowski (1895–1967), a versatile athlete and Home Army officer, was arrested by the Soviet secret police agency (NKVD) in July 1945. He endured 18 months in Vilnius and subsequent camps in Ostashkov and Murmansk. On his return to Poland in July 1948, he worked as a physical education teacher, then as a fencing coach and sports activist, eventually running a farm owing to health reasons.

Most of Poland’s interwar Olympic athletes were exemplary patriots. Not only did they represent their country in international competitions, but they also fought valiantly in defence of their homeland, participating in conspiracies and enduring imprisonment. Thirty-nine Olympic athletes served as officers or non-commissioned officers before the war, naturally taking up arms. Alongside them were ordinary workers, doctors, teachers, farmers and craftspeople, all striving to regain freedom, preserve their national identity and save lives.

Many of these athletes died as soldiers or civilians, in combat or executed. Some were honoured for their dedication and heroism, while others were imprisoned or forgotten under the communist regime. Post-war, some faded into obscurity, dedicating themselves to pursuits unrelated to sport. Others rebuilt Polish sports and pioneered training methods, and a few bridged both paths. The sporting achievements and patriotic attitudes of Olympians such as Janusz Kusociński, Józef Noji, Stanisław Marusarz, Halina Konopacka and Eugeniusz Lokajski remain an inspiration for future generations of athletes, not only in Poland but worldwide.

Loud and silent heroes – even those less celebrated during the communist era, such as those murdered in Katyn and emigrants – are figures worthy of emulation in today’s vastly different world. Their biographies are compelling examples not just of the pursuit of gold medals, but of the steadfast quest for human dignity.

***

Bibliography

Bieszka, A., Organizacja i formy działania w zakresie kultury fizycznej w obozie VII A Murnau. Sprawozdanie dla Międzynarodowego Czerwonego Krzyża , AWF, Warszawa 1970.

Hudycz, T., Wychowanie fizyczne i sport w obozie jenieckim II C Woldenberg , Warszawa 1970.

Jucewicz, A., Olimpijczycy w walce o wolność. ‘50 lat na olimpijskim szlaku’, Warszawa 1969.

Kołbuk, A., Patriotyczne postawy polskich sportowców olimpijczyków w czasie drugiej wojny światowej , ‘Bibliografistyka Pedagogiczna’, 2019.

Matuchniak-Mystowska, A., Sport jeniecki w Oflagach II B Arnswalde, II C Woldenberg, II D Gross Born. Analiza socjologiczna , Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, Łódź 2021.

Skowronek, T., Zapomniane igrzyska , Borne Sulinowo 2014.

Tuszyński, B., Księga sportowców polskich ofiar II wojny światowej 1939–1945, Warszawa 1969.

Tuszyński, B., Kurzyński, H., Leksykon olimpijczyków polskich. Od Chamonix i Paryża do Soczi 1924–2014, Warszawa 2014.

Urban, R., Polscy olimpijczycy w niemieckich obozach jenieckich , ‘Łambinowicki Rocznik Muzealny: jeńcy wojenni w latach II wojny światowej’, Szczecin 2021, 23–53.

Wryk, R., Olimpijczycy Drugiej Rzeczypospolitej , Wydawnictwo Nauka i Innowacje, Poznań 2015.

Wryk, R., Kurzyński, H., Sport olimpijski w Polsce w 1919–1939, Wydawnictwo Poznańskie, Poznań 2006.

Wryk, R., Sport polski w cieniu swastyki. Szkic historiograficzny , ‘Przegląd Zachodni’, Poznań 2018.