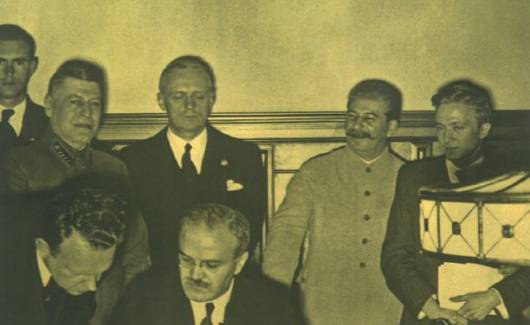

23 August, the day in 1939 when Ribbentrop and Molotov signed the Nazi- Soviet Non-Aggression Pact, gained international recognition in the 1980s. First, in North America, political émigrés from the Soviet Bloc staged public ‘Black Ribbon Day’ ceremonies; this was followed by demonstrations in the Baltic republics of the USSR, culminating in the ‘Baltic Chain’ from Tallinn via Riga to Vilnius in 1989. After the Eastern Enlargement of the European Union in 2004, deputies from Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, the Baltic States and other new member countries in the European Parliament identified 23 August as the lowest common denominator of the enlarged EU’s politics of history. In a discussion process lasting from 2009 to 2011, the Parliament, the Commission and finally the Council of the EU defined 23 August as a ‘Europewide Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Totalitarian Regimes’.

The Battle for Authority of Interpretation

The year 2009 was truly one of multiple European anniversaries: 20 years after the ‘peaceful revolution’ of 1989, 60 years since the foundation of the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany (and also the establishment of the GDR) in 1949, 70 years since the beginning of the Second World War on 1 September 1939, 90 years since the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, 200 years since the foundation of the Grand Duchy of Finland within the Russian Imperial Federation, and 220 years since the French Revolution of 1789, to name only the most important. Amid this spree of jubilees, the 70th anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 23 August 1939 did not have a particularly prominent place in the majority of Europe’s national remembrance cultures, the obvious exceptions being those of the directly affected national societies of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania and Moldova, as well as Finland (and thus, indirectly, Sweden as well). Alongside the looming shadow of the epochal year 1989, it was above all the dominance of the cultural memory of 1 September 1939 – the day of the German invasion of Poland – that eclipsed 23 August. Klaus Zernack has therefore recently classified 1 September 1939 as a day that is ‘today [viewed] worldwide as a date of remembrance for world peace’: 1

In the European perspective there is no need (…) for long discussion as to whether 1 September 1939 – and what followed it for the next six years and after, as the consequences of the Cold War shaped almost the whole century – is an intricate site of memory of a globally comprehended horror story. In the world’s memory of history, however, 1 September 1939 represents the date with the strongest symbolism for the 20th century. In many countries in the world it has been elevated to a day of remembrance to commemorate world peace. Without doubt this is therefore a lieu de mémoire of global significance. 2

The fact that the Polish state ceremony at Westerplatte in Gdańsk on 1 September 2009 attracted worldwide media attention – with German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin as the most prominent guests of Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk – makes this statement just as striking as that of the classification of Jan Rydel, Zernack’s Polish colleague, of 1 September as ‘from the Polish point of view the deepest watershed of the 20th century’.3 In other words, as opposed to 1 September, 23 August is of secondary importance, and this in Poland itself, whereas from the ‘Western European’ perspective it is seen as a primarily, albeit not exclusively (Central and) Eastern European matter. 4 Even in Germany, the former treaty partner, amid the circus of the 20th anniversary of the ‘Peaceful Revolution’, the 70th anniversary of the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Soviet Union, together with the Secret Protocol on the amicable division of Eastern Europe into spheres of influence, was greeted in interested circles with so little media interest that a group of political figures, historians, and intellectuals dealing in history and memory felt compelled to publish an appeal titled ‘Celebrating the year 1989 also means remembering 1939’, and to describe this explicitly as a ‘Declaration to mark the 70th anniversary of the Hitler-Stalin Pact on 23 August 2009’. 5 While this appeal was received with great public interest in Poland, 6 in Germany, to a large degree, it typically enough went unnoticed.

The national publics of the wider Europe were similarly unresponsive to the struggle for authority over the interpretation of the historical-political narrative that was sparked by the European approach to remembering the legacy of Nazism and Stalinism, the focus of which was the Molotov- Ribbentrop Pact as the culmination of both forms of totalitarianism. The actors in this struggle were on the one side political figures dealing in issues of history and memory from Central and Eastern Europe, who found considerable support in Northern Europe and other parts of the continent, and on the other side officials exercising authority over the politics of history of the Russian Federation, such as the president, head of government, ministers, secret service, Duma, parties, the Church, armed forces, media, NGOs and historians. 7 This struggle was fought out in the arenas of the Parliamentary Assemblies of the European Council and the Organisation of Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) – two pan-European institutions of which the Russian Federation was (and still) is a member. On top of this were quite a few bilateral Russian-foreign forums and bodies, such as those with Poland and Germany. However, Moscow had no leverage over the European Union and its Parliament, whose members were able to bring their issues related to the politics of history energetically to the table after their accession in 2004. Accordingly, several years of initiatives culminated in the form of a suggestion to proclaim 23 August the ‘European day of remembrance of the victims of Stalinism and Nazism’, which between 2009 and 2011 the EU transformed into a request to the 27 member states to declare 23 August a Europe-wide day of remembrance ‘of the victims of all totalitarian and authoritarian regimes’. 8 This inflicted a defeat on Moscow at the end of a heavily symbolic defensive battle over history and memory, which at the same time explains the revision of the state history policy of the Russian Federation in the form of an opening outwards and inwards in 2009. Whilst at the beginning of the year a clear hardening was visible, this gave way in the summer and autumn to a pronounced liberalisation with elements of self-criticism – a change of course that continued in 2010 and into 2011. 9

The initiative of the proclamation of 23 August as a day of remembrance for the victims of the two totalitarian dictatorships of 20th-century Europe, both shaped by state terror and mass murder, using the heavily symbolic name ‘Black Ribbon Day’, came from political emigrants in North America who had come from the Baltic States and other Central and Eastern European countries. At the same time as the beginning of perestroika and glasnost in the USSR, on 23 August 1986, the first demonstrations took place in the Canadian capital Ottawa and several large cities in the USA as well as London, Stockholm, and Perth in Australia. Just one year later, in 1987, dissident groups in the Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian Soviet republics dared to hold their first public commemoration services, despite the continuing extremely repressive conditions, in which hundreds and even thousands of people participated. And in 1989, on the 50th anniversary of the Pact, over a million Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians and Russian-speakers sympathetic to the cause formed a 600-kilometre-long human chain – the ‘Baltic Way’ or ‘Baltic Chain’, from Tallinn, via Riga, to Vilnius. Since then, the commemorations of 23 August in the late Soviet era, and the memory of the extremely dangerous conditions under which they were held, have become a pan-Baltic lieu de mémoire.10

The break-up of the Soviet Union, together with the re-establishment of the statehood of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania and the end of Soviet hegemony over East-Central and South-Eastern Europe, led to numerous states in the region (including the new Russian Federation) being admitted into the Council of Europe, the oldest pan-European institution, founded in 1949. Accordingly, this Strasbourg-based international organisation developed into a forum for initiatives that dealt with the politics of the history of the legacy of the communist dictatorships. This particularly applied to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe and its various committees, which sat a number of times a year, their members being drawn from the national parliaments of the member states. By 1996, with Russia and Croatia having recently joined, all the states of East-Central Europe and almost all the successor states of the USSR had become members of the Council; it was in this year that the Parliamentary Assembly first took up the subject of what was to be designated as the ‘legacy of the former communist totalitarian regime’. The applicable ‘Resolution 1096 (1996) on measures to dismantle the heritage of former communist totalitarian systems’ tabled by Central and Eastern European members therefore aimed at decentralisation, demilitarisation, privatisation and de-bureaucratisation as well as transitional justice and the opening of the secret police archives in the course of the transformation process, and only on the margins at ‘a transformation of mentalities (a transformation of hearts and minds)’. 11

Because of its nature, being oriented towards the present and future rather than ‘historical’, the resolution met little resistance from the newly present Russian deputies, particularly as a motion tabled in 1995 by Central and Eastern European, Italian and British deputies on the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact had not been considered by the Parliamentary Assembly. This had addressed ‘a common approach of solidarity in rejecting the two totalitarian systems which gravely undermined the Europe of this century, namely Nazism and Bolshevism, and of condemnation of their complicity which is tragically embodied in the so-called Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, signed on 23 August 1939.’ 12

The European Parliament as a Major Player in the Politics of History

The accession of eight Central and Eastern European states to the European Union on 1 May 2004 – Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Slovenia – now made it possible for these countries to bring their national historical narratives to the forum of the European Parliament. First, however, the parliamentarians of the ‘old’ EU, the ‘EU-15’, laid down a marker for the politics of history. On 27 January 2005, in a programme document titled ‘The Holocaust, antisemitism and racism. European Parliament resolution on remembrance of the Holocaust, anti-semitism and racism’, following the Stockholm Declaration of the International Holocaust Forum of 2000, they proclaimed 27 January – the Day of the Liberation of the Extermination Camp Auschwitz- Birkenau by the Red Army – ‘European Holocaust Memorial Day’ across the whole of the EU. 13 This was a response from the European Parliament to the introduction in 1996 of the Day of Remembrance of the Victims of National Socialism on 27 January in Germany and in 2001 of Holocaust Memorial Day in the United Kingdom, thus contributing to the proclamation of the International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust (International Holocaust Remembrance Day) by the United Nations General Assembly on 1 November 2005. 14

An opportunity for the Central and Eastern European MEPs came a few weeks later in a parliamentary debate on ‘The future of Europe 60 years after the Second World War’. The diverging meanings of the history of violence in the 20th century that dominated in ‘old (Western) Europe’ and ‘New (Central and Eastern) Europe’ now clashed abruptly. In his opening statement, the Council President, the Luxembourger Jean-Claude Juncker, attempted to maintain the balance so as to stress, on the one hand, the contribution of the ‘soldiers of the Red Army’:

What losses! What an excessive number of interrupted life stories amongst the Russians, who contributed 27 million lives to the liberation of Europe! No one needs to harbour a great love – although I do – for the profound and eternal Russian State to acknowledge the fact that Russia deserves well of Europe. 15

On the other hand, he addressed the different nature of the historical experience of Central and Eastern Europe:

The restored freedom at the start of May 1945, however, was not enjoyed in equal measure throughout Europe. Comfortably installed in our old democracies, we were able to live in freedom in Western Europe after the Second World War, and in a state of restored freedom whose price we well know. Those who lived in Central and Eastern Europe, however, did not experience the same level of freedom that we have experienced for 50 years. They were subjected to the law of someone else. The Baltic States, whose arrival into Europe I should like to welcome and to whom I should like to point out how proud we are to have them amongst us, were forcibly integrated into a group that was not their own. They were subjected not to the pax libertatis, but to the pax sovietika that was not their own. Those people and nations that underwent one misfortune after another suffered more than any other European. The other countries of Central and Eastern Europe did not experience that extraordinary capacity for selfdetermination that we were able to experience in our part of Europe. They were not liberated. They had to evolve under the regime of principle imposed on them. 16

In the subsequent debate, described by the conservative Polish member Wojciech Roszkowski as ‘perhaps the most important debate on European identity that has been held for years’, the French communist Francis Wurtz spoke vehemently against ‘excusing the Nazi atrocities by pointing the finger at Stalinist crimes’, since ‘Nazism was neither a dictatorship nor a tyranny like any other, but rather the complete break with society as a whole’.

The Hungarian Fidesz member József Szájer countered: ‘The one who frees the innocent captive from one prison and locks him up in another, is a prison guard, not a liberator’. Practically all the MEPs from Central and Eastern Europe emphasised that focusing on 8 May 1945, regardless of what happened on 23 August 1939 was incomprehensible. Roszkowski argued explicitly against the memory politics of Russia at the time, with its relativisation of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and the crimes of Stalin himself. 17 The ‘European Parliament resolution on the sixtieth anniversary of the end of the Second World War in Europe on 8 May 1945’ adopted on 12 May 2005 accordingly invoked the need for ‘remembering that for some nations the end of the Second World War meant renewed tyranny inflicted by the Stalinist Soviet Union’. 18

The previous day, Russian president Putin had taken the opportunity to once again underline the official position of his country in a press conference, calling the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact ‘a personal matter between Stalin and Hitler’, not of the ‘Soviet people’. On the one hand he described the content of the pact as ‘legally weak’, yet on the other he termed the territorial changes that resulted from it a mere ‘return of the regions’ that had fallen to Germany in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in 1918. With reference to the condemnation of the Pact along with the Secret Protocol by the Second Congress of People’s Deputies of the disintegrating USSR on 24 December 1989, he expressed his annoyance, adding:

What else is wanted then? Are we supposed to condemn it again every year? We consider this subject closed and will not come back to it. We’ve expressed our position on it once, and that’s enough. 19

Russian statements such as this deepened the trench in the politics of history which was dividing the now considerably expanded European Parliament. No small number of Central and East European MEPs saw many of their colleagues from Western Europe as naïve victims of (post-) Soviet propaganda, whereas some West European leftists viewed certain Central and Eastern European right-wingers as notorious Russian haters, even anti- Semites. This became tellingly clear in a plenary debate on 4 July 2006, on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of General Francisco Franco’s 1936 coup in Spain, during which the right-wing nationalist Polish MEP Maciej Marian Giertych described the Caudillo as the saviour of Central and Western Europe from the ‘communist plague’:

The presence of figures such as Franco […] in European politics ensured that Europe maintained its traditional values. We lack such statesmen today. It is with some regret that we observe today the phenomenon of historical revisionism, which portrays all that is traditional and Catholic in an unfavourable light and everything that is secular and socialist in a favourable light. Let us remember that Nazism in Germany and fascism in Italy also had socialist and atheist roots. 20

It was no coincidence that it was a German MEP who hit out vociferously at his Polish colleague: ‘what we have just heard is the spirit of Mr Franco. It was a fascist speech and it has no place in the European Parliament.’ 21

The European Parliament exhibited a broad spectrum of opinions at the time, and its majority followed a balanced line towards the Soviet participation in the history of Europe after 1945. In contrast, in 2006 the members of the Council of Europe continued their course, set ten years earlier, to ‘overcome the legacy of the communist totalitarian regime’. After discussing a report produced by Göran Lindblad, the Swedish member of the Council of Europe Political Affairs Committee, which was unmistakably inspired by the ‘Black Book of Communism’ published in 1997 and prepared by a French-Polish-Czech group of authors, 22 they passed ‘Resolution 1481 (2006) – Need for international condemnation of crimes of totalitarian communist regimes’. This stated that:

2. The totalitarian communist regimes which ruled in central and eastern Europe in the last century, and which are still in power in several countries in the world, have been, without exception, characterised by massive violations of human rights. The violations have differed depending on the culture, country and the historical period and have included individual and collective assassinations and executions, death in concentration camps, starvation, deportations, torture, slave labour and other forms of mass physical terror, persecution on ethnic or religious grounds, violation of freedom of conscience, thought and expression, of freedom of the press, and also lack of political pluralism.

3. The crimes were justified in the name of the class struggle theory and the principle of dictatorship of the proletariat. The interpretation of both principles legitimised the ‘elimination’ of people who were considered harmful to the construction of a new society and, as such, enemies of the totalitarian communist regimes. A vast number of victims in every country concerned were its own nationals. It was the case particularly of the peoples of the former USSR who by far outnumbered other peoples in terms of the number of victims. (…)

7. The Assembly is convinced that the awareness of history is one of the preconditions for avoiding similar crimes in the future. Furthermore, moral assessment and condemnation of crimes committed play an important role in the education of young generations. The clear position of the international community on the past may be a reference for their future actions. (…)

10. The debates and condemnations which have taken place so far at national level in some Council of Europe member states cannot give dispensation to the international community from taking a clear position on the crimes committed by the totalitarian communist regimes. It has a moral obligation to do so without any further delay.

11. The Council of Europe is well placed for such a debate at international level. All former European communist countries, with the exception of Belarus, are now members, and the protection of human rights and the rule of law are basic values for which it stands.

12. Therefore, the Assembly strongly condemns the massive human rights violations committed by the totalitarian communist regimes and expresses sympathy, understanding and recognition to the victims of these crimes.

13. Furthermore, it calls on all communist or post-communist parties in its member states which have not yet done so to reassess the history of communism and their own past, clearly distance themselves from the crimes committed by totalitarian communist regimes and condemn them without any ambiguity.

14. The Assembly believes that this clear position of the international community will pave the way to further reconciliation. Furthermore, it will hopefully encourage historians throughout the world to continue their research aimed at the determination and objective verification of what took place. 23

It is notable that this declaration was passed by an assembly that included members of the communist parties of France, the Russian Federation, Greece and other states, as well as numerous representatives of post-communist parties from Bulgaria, Germany, Poland and elsewhere, without such highly ideologised debates as occurred in the European Parliament the previous year.

The further the jubilee year of 2009 cast its shadow, the more intensive the pan-European actors’ activities in the field of the politics of history became, with those from Central and Eastern Europe again being the driving force. 24 It was thus that, on 3 June 2008, the participants in a conference organised by the government of the Czech Republic, including Václav Havel, Vytautas Landsbergis, Joachim Gauck, the aforementioned Göran Lindblad, and other mostly Czech politicians and intellectuals, passed the ‘Prague Declaration on European Conscience and Communism’, which stated:

1. reaching an all-European understanding that both the Nazi and Communist totalitarian regimes each to be judged by their own terrible merits to be destructive in their policies of systematically applying extreme forms of terror, suppressing all civic and human liberties, starting aggressive wars and, as an inseparable part of their ideologies, exterminating and deporting whole nations and groups of population; and that as such they should be considered to be the main disasters, which blighted the 20th century,

2. recognition that many crimes committed in the name of Communism should be assessed as crimes against humanity serving as a warning for future generations, in the same way Nazi crimes were assessed by the Nuremberg Tribunal,

3. formulation of a common approach regarding crimes of totalitarian regimes, inter alia Communist regimes, and raising a Europe-wide awareness of the Communist crimes in order to clearly define a common attitude towards the crimes of the Communist regimes, (…)

7. recognition of Communism as an integral and horrific part of Europe’s common history, (…)

9. establishment of 23 August, the day of signing of the Hitler- Stalin Pact, known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, as a day of remembrance of the victims of both Nazi and Communist totalitarian regimes, in the same way Europe remembers the victims of the Holocaust on January 27 (…)

15. establishment of an Institute of European Memory and Conscience which would be both - A) a European research institute for totalitarianism studies, developing scientific and educational projects and providing support to networking of national research institutes specialising in the subject of totalitarian experience, B) and a pan-European museum/memorial of victims of all totalitarian regimes, with an aim to memorialise victims of these regimes and raise awareness of the crimes committed by them (…).25

The message that the day of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact should be made an international ‘anti-totalitarian’ day of remembrance was thus sent to Brussels. Katrin Hammerstein and Birgit Hofmann rightly argued in 2009 that ‘The demand “Never again Auschwitz” seems on the European level to be being replaced by the formula “Never again totalitarianism”.’ 26 The symbolic value of 23 August moved in this way over a 20-year-long process into the consciousness of the European public sphere; this was finally reflected in the ‘Declaration of the European Parliament on the Proclamation of 23 August as the European Day of Remembrance for Victims of Stalinism and Nazism’ – and the ‘Central and East European’ rule of three ‘Nazism = Stalinism = Totalitarianism’ had now become an (EU-) European one:

The European Parliament, (…)

– having regard to Resolution 1481 (2006) of the Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly on the need for international condemnation of crimes of totalitarian communist regimes, (…)

A. whereas the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 23 August 1939 between the Soviet Union and Germany divided Europe into two spheres of interest by means of secret additional protocols,

B. whereas the mass deportations, murders and enslavements committed in the context of the acts of aggression by Stalinism and Nazism fall into the category of war crimes and crimes against humanity, (…)

D. whereas the influence and significance of the Soviet order and occupation on and for citizens of the post-Communist States are little known in Europe, (…)

1. Proposes that 23 August be proclaimed European Day of Remembrance for Victims of Stalinism and Nazism, in order to preserve the memory of the victims of mass deportations and exterminations, and at the same time rooting democracy more firmly and reinforcing peace and stability in our continent;

2. Instructs its President to forward this declaration, together with the names of the signatories, to the parliaments of the Member States. 27

It is difficult to say whether in doing this the MEPs simply overlooked the fact that on the list of international days of remembrance 23 August had already been ‘taken’ by UNESCO in 1998, which declared it the ‘International Day of Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition’ with reference to a slave uprising in Santo Domingo in 1791, 28 or whether this coincidence was consciously taken into account. In any case, duplications of days of remembrance by different international organisations are nothing unusual.

One month later the European Parliament took a further step in terms of the politics of memory which was unusual in involving, in contrast to the 2006 debate on the Franco dictatorship, not a member country of the EU, but a non-member state, namely Ukraine. The ‘European Parliament resolution of 23 October 2008 on the commemoration of the Holodomor, the Ukraine artificial famine (1932-1933)’ served primarily to support the reforms of the Ukrainian president and ‘hero’ of the ‘Orange’ democracy movement, Viktor Yushchenko, yet on the other hand showed an approach that was construed as hostile in Russia, for it stated that ‘the Holodomor famine of 1932-1933, which caused the deaths of millions of Ukrainians, was cynically and cruelly planned by Stalin’s regime in order to force through the Soviet Union’s policy of collectivisation of agriculture against the will of the rural population in Ukraine’, and called on ‘the countries which emerged following the break-up of the Soviet Union to open up their archives on the Holodomor in Ukraine of 1932-1933 to comprehensive scrutiny so that all the causes and consequences can be revealed and fully investigated’. 29 Even if the Holodomor was not, in accordance with the terminology prescribed by the Ukrainian president, described as genocide (henotsyd), but ‘only’ as ‘an appalling crime against the Ukrainian people, and against humanity’, the declaration was interpreted by authorities in the field of the politics of history in Moscow as a challenge and ‘interference’ in post-Soviet ‘domestic affairs’.30 A further reason for the increased attention devoted by the EU with regard to coming to terms with the past à la russe alongside the developments in Ukraine was the Russian-Estonian conflict, which was triggered by the powerful protest that Moscow issued in response to the moving of a Soviet war memorial in 2007 in Tallinn, the capital of the EU member state Estonia.31 The way in which Russia tried to force its small neighbour to conform to its own memory narrative not only led to surprise and criticism within EU circles, but also provoked infuriation towards the attitude of Estonia and its kowtowing to Moscow.

The two decisions of the European Parliament of September and October 2008 on 23 August and the Holodomor, together with the other characteristic responses to the Holocaust, the end of the war in 1945 and the Franco dictatorship quoted above, and, moreover, the one made in 2009 to the Serb massacre of 8000 Bosnian Muslims on 11 July 1995 in Srebrenica,32 formed part of an ambitious plan by MEPs, which can be described as a ‘to-do list’ for the ‘EU-standard’ of dealing with dictatorial pasts. Within the parliament, the body responsible for coordinating these issues, there has since May 2010 been an all-party informal group of 35 MEPs chaired by the suitably distinguished former Latvian foreign minister and EU commissioner Sandra Kalniete. The group has given itself the task of promoting the ‘reconciliation of European histories’ (in the plural), and in its ranks include (or have included) such competent and respected members as the Dutch historian of Eastern Europe Bastiaan Belder (who died in 2011), the Hungarian expert on minority rights Kinga Gál, and the German former president of the European Parliament Hans-Gert Pöttering. 33 At the same time, the Parliament is clearly showing through its actions that it feels responsible for the whole political field of coming to terms with the past in Europe – and this is not only confined to EU member states, but also to states such as the specifically named Russian Federation – and that it is determined to create the appropriate instruments and to prompt the EU Commission to make the necessary tools available. The proclamation of 23 August as the ‘Europe-wide Remembrance Day for the victims of all totalitarian and authoritarian regimes, to be commemorated with dignity and impartiality’ is therefore accorded a prominent role. This extremely substantial list of tasks was made public in the extensive ‘European Parliament resolution of 2 April 2009 on European conscience and totalitarianism’:

The European Parliament, (…)

– having regard to Resolution 1481 of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe of 25 January 2006 on the need for international condemnation of the crimes of totalitarian Communist regimes,

– having regard to its declaration of 23 September 2008 on the proclamation of 23 August as European Day of Remembrance for Victims of Stalinism and Nazism,

– having regard to its many previous resolutions on democracy and respect for fundamental rights and freedoms, including that of 12 May 2005 on the 60th anniversary of the end of the Second World War in Europe on 8 May 1945, that of 23 October 2008 on the commemoration of the Holodomor, and that of 15 January 2009 on Srebrenica,

– having regard to the Truth and Justice Commissions established in various parts of the world, which have helped those who have lived under numerous former authoritarian and totalitarian regimes to overcome their differences and achieve reconciliation,

– having regard to the statements made by its President and the political groups on 4 July 2006, 70 years after General Franco’s coup d’état in Spain, (…)

A. whereas historians agree that fully objective interpretations of historical facts are not possible and objective historical narratives do not exist; whereas, nevertheless, professional historians use scientific tools to study the past, and try to be as impartial as possible,

B. whereas no political body or political party has a monopoly on interpreting history, and such bodies and parties cannot claim to be objective,

C. whereas official political interpretations of historical facts should not be imposed by means of majority decisions of parliaments; whereas a parliament cannot legislate on the past, (…)

E. whereas misinterpretations of history can fuel exclusivist policies and thereby incite hatred and racism,

F. whereas the memories of Europe’s tragic past must be kept alive in order to honour the victims, condemn the perpetrators and lay the foundations for reconciliation based on truth and remembrance,

G. whereas millions of victims were deported, imprisoned, tortured and murdered by totalitarian and authoritarian regimes during the 20th century in Europe; whereas the uniqueness of the Holocaust must nevertheless be acknowledged,

H. whereas the dominant historical experience of Western Europe was Nazism, and whereas Central and Eastern European countries have experienced both Communism and Nazism; whereas understanding has to be promoted in relation to the double legacy of dictatorship borne by these countries,

I. whereas from the outset European integration has been a response to the suffering inflicted by two world wars and the Nazi tyranny that led to the Holocaust and to the expansion of totalitarian and undemocratic Communist regimes in Central and Eastern Europe, as well as a way of overcoming deep divisions and hostility in Europe through cooperation and integration and of ending war and securing democracy in Europe,

J. whereas the process of European integration has been successful and has now led to a European Union that encompasses the countries of Central and Eastern Europe which lived under Communist regimes from the end of World War II until the early 1990s, and whereas the earlier accessions of Greece, Spain and Portugal, which suffered under longlasting fascist regimes, helped secure democracy in the south of Europe,

K. whereas Europe will not be united unless it is able to form a common view of its history, recognises Nazism, Stalinism and fascist and Communist regimes as a common legacy and brings about an honest and thorough debate on their crimes in the past century,

L. whereas in 2009 a reunited Europe will celebrate the 20th anniversary of the collapse of the Communist dictatorships in Central and Eastern Europe and the fall of the Berlin Wall, which should provide both an opportunity to enhance awareness of the past and recognise the role of democratic citizens’ initiatives, and an incentive to strengthen feelings of togetherness and cohesion,

M. whereas it is also important to remember those who actively opposed totalitarian rule and who should take their place in the consciousness of Europeans as the heroes of the totalitarian age because of their dedication, faithfulness to ideals, honour and courage,

N. whereas from the perspective of the victims it is immaterial which regime deprived them of their liberty or tortured or murdered them for whatever reason,

1. Expresses respect for all victims of totalitarian and undemocratic regimes in Europe and pays tribute to those who fought against tyranny and oppression;

2. Renews its commitment to a peaceful and prosperous Europe founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights;

3. Underlines the importance of keeping the memories of the past alive, because there can be no reconciliation without truth and remembrance; reconfirms its united stand against all totalitarian rule from whatever ideological background;

4. Recalls that the most recent crimes against humanity and acts of genocide in Europe were still taking place in July 1995 and that constant vigilance is needed to fight undemocratic, xenophobic, authoritarian and totalitarian ideas and tendencies;

5. Underlines that, in order to strengthen European awareness of crimes committed by totalitarian and undemocratic regimes, documentation of, and accounts testifying to, Europe’s troubled past must be supported, as there can be no reconciliation without remembrance;

6. Regrets that, 20 years after the collapse of the Communist dictatorships in Central and Eastern Europe, access to documents that are of personal relevance or needed for scientific research is still unduly restricted in some Member States; calls for a genuine effort in all Member States towards opening up archives, including those of the former internal security services, secret police and intelligence agencies, although steps must be taken to ensure that this process is not abused for political purposes;

7. Condemns strongly and unequivocally all crimes against humanity and the massive human rights violations committed by all totalitarian and authoritarian regimes; extends to the victims of these crimes and their family members its sympathy, understanding and recognition of their suffering;

8. Declares that European integration as a model of peace and reconciliation represents a free choice by the peoples of Europe to commit to a shared future, and that the European Union has a particular responsibility to promote and safeguard democracy, respect for human rights and the rule of law, both inside and outside the European Union;

9. Calls on the Commission and the Member States to make further efforts to strengthen the teaching of European history and to underline the historic achievement of European integration and the stark contrast between the tragic past and the peaceful and democratic social order in today’s European Union;

10. Believes that appropriate preservation of historical memory, a comprehensive reassessment of European history and Europe-wide recognition of all historical aspects of modern Europe will strengthen European integration;

11. Calls in this connection on the Council and the Commission to support and defend the activities of non-governmental organisations, such as Memorial in the Russian Federation, that are actively engaged in researching and collecting documents related to the crimes committed during the Stalinist period;

12. Reiterates its consistent support for strengthened international justice;

13. Calls for the establishment of a Platform of European Memory and Conscience to provide support for networking and cooperation among national research institutes specialising in the subject of totalitarian history, and for the creation of a pan-European documentation centre/memorial for the victims of all totalitarian regimes;

14. Calls for a strengthening of the existing relevant financial instruments with a view to providing support for professional historical research on the issues outlined above;

15. Calls for the proclamation of 23 August as a Europe-wide Day of Remembrance for the victims of all totalitarian and authoritarian regimes, to be commemorated with dignity and impartiality;

16. Is convinced that the ultimate goal of disclosure and assessment of the crimes committed by the Communist totalitarian regimes is reconciliation, which can be achieved by admitting responsibility, asking for forgiveness and fostering moral renewal;

17. Instructs its President to forward this resolution to the Council, the Commission, the parliaments of the Member States, the governments and parliaments of the candidate countries, the governments and parliaments of the countries associated with the European Union, and the governments and parliaments of the Members of the Council of Europe.34

With this resolution, whose numerous demands were, as will be shown, generally accepted in 2010 by the Commission and in 2011 by the Council of the EU, the European Union proclaimed itself the central authority for the politics of history with pan-European responsibility and competence, thus de facto withdrawing another policy area from the Council of Europe - which had in any case been fading since 2004 in terms of competences, and in the politics of history had frequently been thwarted by Russia and Turkey. This became possible first because of the greater legitimacy, better infrastructure and incomparably greater financial resources of Brussels, and second as a result of the fact that the Central and Eastern European initiatives regarding the politics of history within the EU framework did not meet the resistance of Russia.

The ‘anti-totalitarian’ resolution of April 2009 did, however, meet with vehement ‘Western’ resistance, with the argument being that the raising of 23 August to the status of an EU day of remembrance unacceptably devalued the significance of the 27 January memorial. In this view, the parallel remembrance of the victims of both forms of totalitarianism represented a qualification of the Holocaust as an unprecedented breach of civilisation through a certain de-contextualisation. Yehuda Bauer, one of the initiators of the Task Force for International Cooperation on Holocaust Education, Remembrance, and Research, founded in 1998, stated in direct reference to the resolution:

The two regimes were both totalitarian, and yet quite different. The greater threat to all of humanity was Nazi Germany, and it was the Soviet Army that liberated Eastern Europe, was the central force that defeated Nazi Germany, and thus saved Europe and the world from the Nazi nightmare. In fact, unintentionally, the Soviets saved the Baltic nations, the Poles, the Ukrainians, the Czechs, and others, from an intended extension of Nazi genocide to these nationalities. This was not intended to lead to total physical annihilation, as with the Jews, but to a disappearance of these groups ‘as such’. The EU statement, implying a straightforward parallel between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, therefore presents an a-historic and distorted picture. (…) World War II was started by Nazi Germany, not the Soviet Union, and the responsibility of the 35 million dead in Europe, 29 million of them non-Jews, is that of Nazi Germany, not Stalin. To commemorate victims equally is a distortion. (…) One certainly should remember the victims of the Soviet regime, and there is every justification for designating special memorials and events to do so. But to put the two regimes on the same level and commemorating the different crimes on the same occasion is totally unacceptable.35

The Austrian historian Heidemarie Uhl, according to whom the remembrance day of 23 August represented an ‘antithesis’ to 27 January, as it was connected to it by an image of history ‘that denies the recognition of the Holocaust as the central point of reference of a European historical consciousness’, added a further argument to Bauer’s criticism:

In the European memory of the Holocaust remembrance of the victims is connected with the question of the involvement of one’s own society in the Nazi atrocities, and memory is understood as the duty to fight against racism, anti-Semitism, the discrimination of minorities based on ethnic, religious, sexual categories. In the remembrance culture of the post- 1989 societies one’s ‘own people’ is seen as an innocent victim of the cruel suppression from outside, [and] the involvement of [one’s] own society in the communist system of rule can in this way be externalised. What can be observed in the post-communist countries is in a certain sense a déjà vu of the stories of victims as we know them from the European postwar myths and the conquering of which is the precondition for the new European memory culture. Making the model of the post-war myths the basis of a pan-European remembrance day rather achieves the opposite: the rifts between the Western European and the post-communist memory culture are likely to deepen.36

Meanwhile, the leader of the Brandenburg Memorials Foundation, Günter Morsch, lamented – with pro-Russian and anti-Polish undertones – the fact that ‘the anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact is misused as a fight over the interpretation of the politics of memory’:

If it was really just about including the victims of communism in the memory, the date of the October Revolution in 1917 could have been chosen. Yet the emphasis on the Molotov- Ribbentrop Pact devalues 1 September, that is the actual beginning of the Second World War, and qualifies 27 January as a day of remembrance for all Nazi victims. One gets the impression that the war and genocide are the result of a conflict in which the totalitarian states on the one side were confronted with the democratic states on the other. Nothing could be less true. The Nazi decision to invade Poland was certain from 1933, whereas until the Munich Agreement of 1938 the Soviets were in serious negotiations with the Western powers and Poland. Poland too was an authoritarian state which until the beginning of 1939 fostered friendly relations with the ‘Third Reich’ and in November 1938 had a military part to play in the division of the democratic Czechoslovakia. The attempt to create a culture of anti-totalitarian remembrance therefore accepts an alarming decontextualisation and homogenisation, the consequences of which are immeasurable. Anybody wishing to learn from history for the future development of a common European future must not pay this price.37

However, these misgivings do not provoke much of a response from many people in European politics. Moscow greeted the resolution of the European Parliament not with open criticism, but with sublimated annoyance that the EU, acting as the ‘conscience of Europe’, wanted to ‘support and defend’ a Russian NGO like MEMORIAL – from whom? – was interpreted by the so-called Russian ‘power vertical’ as just as much of a provocation as the demand, which had been raised again, for 23 August to be treated as a Europe-wide ‘anti-totalitarian’ remembrance day. Yet from Moscow’s point of view it was even worse when the Parliamentary Assembly of the OSCE – of which the Russian Federation is a founding member, as well as being, in its own perception, one of the heavyweights in this international organisation ranging ‘from Vancouver to Vladivostok’ – declared itself in favour of 23 August as a European day of remembrance as well as a parallel condemnation of Nazism and Stalinism at its session in late June/early July 2009 in Vilnius. Its ‘Resolution on Europe – divided and reunified’, tabled by Slovenia and Lithuania, it stated:

3. Noting that in the twentieth century European countries experienced two major totalitarian regimes, Nazi and Stalinist, which brought about genocide, violations of human rights and freedoms, war crimes and crimes against humanity, […]

10. Recalling the initiative of the European Parliament to proclaim 23 August, when the Ribbentrop–Molotov Pact was signed 70 years ago, as a Europe-wide Day of Remembrance for Victims of Stalinism and Nazism, in order to preserve the memory of the victims of mass deportations and exterminations, The OSCE Parliamentary Assembly:

11. Reconfirms its united stand against all totalitarian rule from whatever ideological background; (…)

13. Urges the participating States:

a. to continue research into and raise public awareness of the totalitarian legacy;

b. to develop and improve educational tools, programmes and activities, most notably for younger generations, on totalitarian history, human dignity, human rights and fundamental freedoms, pluralism, democracy and tolerance;

c. to promote and support activities of NGOs which are engaged in areas of research and raising public awareness about crimes committed by totalitarian regimes; (…)

16. Reiterates its call upon all participating States to open their historical and political archives;

17. Expresses deep concern at the glorification of the totalitarian regimes, including the holding of public demonstrations glorifying the Nazi or Stalinist past (…).38

The resolution was passed with 213 votes in favour to eight against, with four abstentions. However, 93 members, probably including all the Russians, Kazakhs, Tajiks, Uzbeks, Turkmens, Kyrgyz and most of the Ukrainians, Azerbaijanis and Armenians, did not take part in the vote. The protests from Moscow appeared particularly weak as they came only from the Duma. The reason for this was the dramatic changes that were taking place in the domestic and external politics of history of the Russian Federation in the summer of 2009.

Since the declaration of the European Parliament regarding 23 August made on 23 September 2008, a whole series of bodies dealing with the politics of history in Russia had realised that the transatlantic anti-Hitler coalition, which apart from a few cracks and breaches was still visible on 9 May 2005 at the ceremony in Red Square to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany, was now crumbling. While in Moscow in 2005 only the Latvian president, Vaira Vīķe-Freiberga, had demanded an apology from Russia for the Molotov- Ribbentrop Pact (as well as for the renewed annexation, camouflaged as ‘liberation’, of the Baltic States by the USSR in 1944),39 the parliament of a European conglomerate of states numbering 27 members as well, indirectly, as the parliamentary pillars of the OSCE, were now proclaiming 23 August as a pan-European day of remembrance. And this was done with some success, as the 70th anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in 2009 was celebrated publicly not only by the countries that were in Russian eyes the ‘usual suspects’ – Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Moldova and Georgia – but moreover by Sweden, Slovenia, the Czech Republic and even Bulgaria as well.

Jerzy Buzek, the liberal Polish European Parliament president who had emerged from the Solidarity movement, crowned the ‘anti-totalitarian’ memory politics of Central and Eastern Europeans in October 2009 by making the Brussels parliament building available as a venue for an international conference organised by the three Baltic States with the title ‘Europe 70 years after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact’. In his opening address Buzek recalled the historical occurrence, according to the Central and Eastern European interpretation, in distinct words:

In August 1939 when the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact was signed to the great shock of the world’s democracies, Time Magazine called it the ‘Communazi Pact’, perhaps a better name for a deal between two totalitarian regimes who proceeded to divide Central and Eastern Europe between themselves. Poland was divided between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, Finland lost 10% of its territory and 12% of its population, Eastern and Northern Romania, as well as the three Baltic States were directly annexed by the Soviet Union. Up to 700,000 Estonians, Lithuanians and Latvians were deported, from a population of six million. In Poland, some 1.5 million people were deported, of these 760,000 died, many of them children. When we are looking at these figures, we can imagine the scale of the whole tragic story. One in ten adult males was arrested; many were executed in a policy of decapitating the local elites. In April, the European Parliament adopted its resolution on ‘European Conscience and Totalitarianism’, which called for the proclamation of August 23rd as a Europe-wide Day of Remembrance for the victims of all totalitarian and authoritarian regimes, and called on the European public to commemorate these victims with dignity and impartiality. We can never forget those victims, for they are a reminder of where we come from, and show us how much we have achieved.40

And to the ‘Dear Friends’ gathered in the European Parliament building, he described an arc from 1939 via 2004 to 2009:

When the new member states joined five years ago, we brought with us our own history and our own stories; one of those tragic stories was the ‘Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact’. (…) Today we are a reunited and integrated continent because we have learnt the lessons of the Second World War, and the pact that allowed it to happen.41

The remembrance day then acquired a transatlantic dimension a few weeks later through the unanimously passed resolution of the Canadian lower chamber of 30 November 2009, which declared that they were cognisant of the ‘infamous pact between the Nazi and Soviet Communist regimes’, and that 23 August would be the ‘Canadian Day of remembrance of the victims of the Nazi and Soviet atrocities’, designated as ‘Black Ribbon Day’.

RESOLUTION TO ESTABLISH AN ANNUAL DAY OF REMEMBRANCE FOR THE VICTIMS OF EUROPE’S TOTALITARIAN REGIMES

1) WHEREAS the Government of Canada has actively advocated for and continues to support the principals enshrined by The United Nations Universal Declaration on Human Rights and The United Nations General Assembly Resolution 260 (III) A of 9 December 1948;

2) WHEREAS the extreme forms of totalitarian rule practised by the Nazi and Communist dictatorships led to premeditated and vast crimes committed against millions of human beings and their basic and inalienable rights on a scale unseen before in history;

3) WHEREAS hundreds of thousands of human beings, fleeing the Nazi and Soviet Communist crimes, sought and found refuge in Canada;

4) WHEREAS the millions of Canadians of Eastern and Central European descent whose families have been directly affected by Nazi and/or Communist crimes have made unique and significant, cultural, economic, social and other contributions to help build the Canada we know today;

5) WHEREAS 20 years after the fall of the totalitarian Communist regimes in Europe, knowledge among Canadians about the totalitarian regimes which terrorised their fellow citizens in Central and Eastern Europe for more than 40 years in the form of systematic and ruthless military, economic and political repression of the people by means of arbitrary executions, mass arrests, deportations, the suppression of free expression, private property and civil society and the destruction of cultural and moral identity and which deprived the vast majority of the peoples of Central and Eastern Europe of their basic human rights and dignity, separating them from the democratic world by means of the Iron Curtain and the Berlin Wall, is still alarmingly superficial and inadequate;

6) WHEREAS Canadians were instrumental during the 1980s in raising global awareness of crimes committed by European totalitarian Nazi and Communist regimes by founding an annual ‘Black Ribbon Day’ on 23 August , to commemorate the legal partnership of these two regimes through the infamous Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and its secret protocols;

BE IT RESOLVED THAT every victim of any totalitarian regime has the same human dignity and deserves justice, remembrance and recognition by the Parliament and the government of Canada, in efforts to ensure that such crimes and events are never again repeated;

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED THAT the Parliament and the Government of Canada unequivocally condemn the crimes against humanity committed by totalitarian Nazi and Communist regimes and offer the victims of these crimes and their family members sympathy, understanding and recognition for their suffering;

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED THAT the Government of Canada establish an annual Canadian Day of Remembrance for the victims of Nazi and Soviet Communist crimes on 23 August, called ‘Black Ribbon Day,’ to coincide with the anniversary of the signing of the infamous pact between the Nazi and Soviet Communist regimes.42

The anchoring that has now occurred of 23 August as an ‘anti-totalitarian’ international day of remembrance, which Russian diplomacy was unable to prevent, has had two entirely different, indeed opposite effects: firstly, Russia reacted by isolating itself and displaying aggressive outward signals, and secondly came a reinterpretation of the country’s own imperial and national history based on a new orientation of the politics of history that were accompanied with clear signs of a readiness to make outward concessions.43 The latter tendency was carried forward by an internal Russian debate, also culminating in 2009, on the topic of ‘victory without Stalin?’ Was Stalin the ‘architect of the victory’ of 9 May 1945, or did the Russian ‘people’ – or to use the earlier term ‘the peoples of the Soviet Union’, or as it is now called, the ‘Russian nation’44 – achieve this victory ‘in spite of Stalin’? This question was accorded a double significance when ‘the victory’ in the ‘Great Patriotic War 1941-1945’ was also ascribed the function of a foundation myth of the Russian Federation – once the use of the Soviet founding myth of the ‘Great Socialist October Revolution’ was discontinued for reasons of ideology. In other words: in the Russian discourse on the Soviet-German pact whose name there is known in the order ‘Ribbentrop-Molotov’, together with the Secret Protocol, the question was and remains not only the role to be ascribed to Stalin in the official national memory of the war, but much more the raison d’être of this, the largest product of the break-up of the Soviet Union, and the cement of an identity bound by memory that is intended to hold together the particularly disparate federation of Russians and numerous non-Russians.

In his contribution to this volume, Wolfram von Scheliha traces how in 2009 President Dmitry A. Medvedev, with the acceptance of his predecessor Prime Minister Putin, despite considerable opposition, drafted and introduced a new approach to the politics of history, both domestically and for international use. Von Scheliha arrives at the surprising and at the same time convincing conclusion that the formation on 15 May 2009 of a ‘President of the Russian Federation’s Commission for the Struggle against Attempts at Falsification of History Damaging Russia’, which met with harsh criticism and great misgivings, especially in Central and Eastern Europe and Germany, was the result of liberal, even ‘pro-European’ forces in the Kremlin who were successfully keeping in check dogmatists nostalgic for Soviet times.45 Indeed, the president subsequently went out on a limb in terms of memory issues in a way that justifies this interpretation. ‘Simply put,’ said Medvedev in a newspaper interview the day before ‘Victory Day’ in 2010, ‘the regime that was established in the USSR can only be described as totalitarian.’ At the same time, he rejected the (post-) Soviet interpretation of 9 May, and thus indirectly also the Russian interpretation of the ‘Great Patriotic War 1941-1945’:

For quite some time the war was perceived exclusively as a Great Victory of the Soviet people and the Red Army. But the war also stands for an immense number of victims and for the colossal losses that the Soviet people suffered together with other European countries. (…) There are absolutely evident facts: the Great Patriotic War was won by our people, not Stalin and not even the military, with all the importance of what they achieved. (…) If we speak of the state evaluation of how Stalin is to be appraised through the leadership of the country in the last years, from the moment of the establishment of the new Russian state, this meaning is clear: Stalin committed an abundance of crimes towards his people. 46

In the same interview, however, Medvedev said that ‘those who place the role of the Red Army and those of the Fascist occupiers on one and the same level are committing a moral crime’, in conjunction with criticism of the Baltic states and praise for the reunified Germany.47

A minor sensation was caused by Medvedev’s decision to invite the chairman of MEMORIAL, Arseny Roginsky, to cooperate with the Presidential Council in working on the development of civil society and on human rights. At a session of this body on 1 February 2011 in Ekaterinburg, the two discussed a memorandum prepared by MEMORIAL, ‘The Immortalisation of the Remembrance of the Victims of the Totalitarian Regime and National Reconciliation’, which demanded financial support for surviving victims of gulags and their full legal rehabilitation, and likewise the establishment of monuments and memorials in visible locations in the public space, the creation of a database of victims, free access to the files of the NKVD secret police, and a ‘political-legal evaluation of the crimes of the communist regime’.48 Roginsky himself, however, was sceptical regarding the seriousness of Medvedev’s liberalisation in memory politics. According to him, the president and prime minister were now acting as ‘anti-Stalinists’ as well as proponents of an explicitly state-Russian, not ethnoculturally Russian national identity, because they feared an excessive strengthening of Stalinist and Russian nationalist forces in the country.49

The state of affairs in 2011

The aforesaid resolution of the European Parliament of 2 April 2009 on the ‘Conscience of Europe and on Totalitarianism’, along with the Council of the EU’s demand in November 2008 to assess the need for EU guidelines against the trivialisation of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes, prompted the EU Commission to intensify its activities. Having already held a seminar in November 2007 on the question ‘How to deal with the totalitarian memory of Europe: Victims and reconciliation’, they commissioned in 2009 a comprehensive study ‘on how the memory of crimes committed by totalitarian regimes in Europe is dealt with in the Member States’, which was submitted in early 2010. 50 Based partly on this, the EU Commission produced a report titled ‘The memory of the crimes committed by totalitarian regimes in Europe’, which was presented to the Parliament and Council in December 2010. In this they were able to report that five member states – Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovenia and Sweden – had transferred the remembrance day of 23 August stipulated by the European Parliament to their national legislatures and recommend that further member states ‘examine the possibility to adhere to this initiative in the light of their own history and specificities’. The Commission also listed those aid programmes whose money could be used for measures of this kind, including the ‘Active European Remembrance’ action of the Europe for Citizens programme, in the framework of which the Platform of European Memory and Conscience supported by the Parliament could also be financed.51 In June 2011, in connection with the aforementioned Commission report of 2010 and the Parliament resolution of 2009, the EU Council passed its ‘conclusions on the memory of the crimes committed by totalitarian regimes in Europe’:

The Council of the European Union

Considering that many Member States have experienced a tragic past caused by totalitarian regimes, be it communist, national socialist or of any other nature, which have resulted in violations of fundamental rights and in the complete denial of human dignity; (…)

Noting, that totalitarian regimes in Europe, although different in their origins, political justification and expression, form part of Europe’s shared history; (…)

4. Highlights the Europe-wide Day of Remembrance of the victims of the totalitarian regimes (23 August) and invites Member States to consider how to commemorate it, in the light of their own history and specificities; (…)

7. Invites the Commission to pay attention to the questions of the participation of smaller organisations to EU financial programmes, including schools and higher education institutions, as well as to examine how to foster participation of the beneficiaries from the Eastern partnership countries and Russia in common initiatives and project financed by these programmes. (…)

9. Invites all interested parties to make full use of existing EU programmes to establish a Platform of European Memory and Conscience to provide support for current and future networking and cooperation among national research institutes specialising in the subject of totalitarian history.52

As a result, within three years the project of the proclamation of 23 August, a Europe-wide day of remembrance had successfully negotiated the path through the EU bodies – from the Parliament, via the Commission, to the Council. And so, together with the resolution of the Canadian parliament from 2009, the last stage of the rise of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact as a Euro-Atlantic lieu de mémoire, together with the remembrance day of 23 August, was complete. The first stage was the time of perestroika, leading to the negotiated transitions of 1989. The second, in the 1990s, was that of the European Council’s dealing with the legacy of the ‘ totalitarian communist regime’. The third began in 2004, with the accession of the Central and Eastern European states to the EU and the subsequent debates in the European Parliament. The fourth was the stage described above, lasting from 2008 to 2011.

All of this influenced the domestic as well as the external policy of the Russian Federation in an increasingly polarising sense: the European Parliament’s call to declare 23 August as a Europe-wide day of remembrance led in the build-up to the 70th anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in Russia to a battle for authority over interpretation between the nationalist idolisers of Stalin and the power pragmatists, who viewed themselves as liberals, in which President Medvedev, who to date has in the public space been numbered among the latter camp, was able to come out on top. While the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact has by no means lost its quality as an expressly non-site of memory in the CIS (with the exception of Moldova), it is no longer a taboo subject in Russia’s external memory politics. The reasons for this include the debate raging internally in Russia since 2011 about what is now known as the de-Stalinisation (destalinizaciya) of the country; the palpable improvement in Russian-Polish relations since 2009 – strengthened since the Smolensk plane disaster of April 2010, and including the subject of Katyń, which is comparable in its shattering effect to the 1939 Pact; the German-Russian special relationship, recently described as a ‘modernisation partnership’; and finally the debates in the pan-European forums of the European Council and the OSCE – and especially the intensified activities of the European Union since 2004 in the field of the politics of history.

It is important to emphasise once again, however, that only in exceptional cases do the negotiations at the EU, OSCE and European Council level and their effects, in terms of the politics of history, have repercussions in the media, public sphere and politics (as well as in the academic study of memory). 53 The culture of remembrance in Europe as well as the rest of the world is first and foremost a national matter, which as a rule has few transnational common spaces. Like Europe Day on 9 May, or 27 January, 23 August as Black Ribbon Day or the European Day of Remembrance of the Victims of the Stalinist and Nazi Atrocities remains in the shadows of most national cultures of remembrance in the Northern Hemisphere. The fact that it has over the course of almost three decades even been anchored as such must, however, be assessed as a genuine success of pan-European /trans-Atlantic, and here primarily Central and Eastern European, politics of history and memory. The misgivings of intellectuals and academics, based on reasons pertaining to teaching about memory, on the perceived devaluation of 27 January, and even the implicit equation of the Holocaust on the one hand with the gulags, Holodomor and the Great Terror on the other, prove to be of little political importance given the broad transnational- parliamentary consensus of 23 August. Yet whether the new Euro- Atlantic day of remembrance will turn out to be of great significance in all or at least the majority of the cultures of memory of the national societies of Europe, Eurasia, and North America is a question to which the answer lies in the future.

Prof. Dr. Stefan Troebst, University of Leipzig. Born in 1955 in Heidelberg, 1974-1984 Studies in History, Slavic Studies, Balkanologie and Islamic Studies at the Free University Berlin and at the universities of Tübingen, Sofia (Bulgaria), Skopje (Yugoslavia, now Macedonia) and at Indiana University Bloomington, (USA) 1984; 1984-1992 Wiss. Staff and Assistant Professor of East European History at the Eastern European Institute at the Free University of Berlin, Since 1999, Professor of Cultural Studies at the University of Leipzig, East Central Europe, also a senior fellow at Geisteswissenschaftliche Zentrum Geschichte und Kultur Ostmitteleuropas.

ENDNOTES

1. K. Zernack, ‘1. September 1939: als hochstes Stadium “Negativer Polenpolitik”’, in: E. Francois and U. Puschner (eds), Erinnerungstage. Wendepunkte der Geschichte von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart (Munchen, 2010), pp. 305-318 and 437-440, here p. 317.

2. Ibid., p. 305.

3. J. Rydel, ‘Der 1. September als ein Fokus der Erinnerung’, in: S. Raabe and P. Womela (eds), Der Hitler-Stalin-Pakt und der Beginn des Zweiten Weltkrieges / Pakt Hitler- Stalin i wybuch II Wojny Światowej (Warszawa, 2009), pp. 7-12, here p. 12. The Warsaw historian Jerzy Kochanowski, however, has at the same time pointed out that the Polish lieu de mémoire ‘1 September 1939’ has in the meantime been given stiff competition by that of ‘17 September 1939’ – the day of the Red Army invasion of eastern Poland – ‘The ‘German’ part of the Polish history of World War II has been pushed to the side to such a degree that one might gain the impression that the war began not on 1 September 1939, but 17 days later.’ Cf. id., ‘Der Kriegsbeginn in der polnischen Erinnerung’, in: Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte 36-37 (2009), pp. 6-13, here p. 12.

4. S. Troebst, ‘Der 23. August 1939 – ein europaischer lieu de mémoire’, Osteuropa 59 (2009) 7-8, pp. 249-256, also www.eurozine.com, accessed: 30.06.2011.

5. ‘Das Jahr 1989 feiern, heist auch, sich an 1939 zu erinnern! Eine Erklarung zum 70. Jahrestag des Hitler-Stalin-Pakts’. Berlin, 23. August 2009, Die Zeit 35 (20.08.2009), pp. 22. See also www.23august1939.de, accessed 01.06.2011. You can also find versions in German, Russian, Polish, Czech and Hungarian here.

6. ‘Przepraszamy za 1939, dziękujemy za 1989. List niemieckich intelektualistow w 70. rocznicę II wojny światowej’, Gazeta Wyborcza, 21.08.2009, p. 1, wyborcza.pl, accessed 26. 06. 2011.

7. On this and other dividing lines in memory culture in Europe cf. C.S. Maier, ‘Heises und kaltes Gedachtnis. Zur politischen Halbwertzeit des faschistischen und kommunistischen Gedachtnisses’, in: Transit. Europäische Revue 22 (2001/2002), pp. 153-165; S. Troebst, ‘Holodomor oder Holocaust?’, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung 152 (04.07.2005), p. 8; id., ‘Jalta versus Stalingrad, GULag versus Holocaust. Konfligierende Erinnerungskulturen im groseren Europa’, Berliner Journal für Soziologie 15 (2005), pp. 381-400; U. Ackermann, ‘Das gespaltene Gedenken. Eine gesamteuropaische Erinnerungskultur ist noch nicht in Sicht’, Internationale Politik 61 (2006) 5, pp. 44- 48; H.-A. Winkler, ‘Erinnerungswelten im Widerstreit. Europas langer Weg zu einem gemeinsamen Bild von Jahrhundert der Extreme’, in: B. Kauffmann and B. Kerski (eds), Antisemitismus und Erinnerungskulturen im postkommunistischen Europa (Osnabruck, 2006), pp. 105-116.

8. For the context cf. K. Hammerstein and B. Hofmann, ‘Europaische “Interventionen”: Resolutionen und Initiativen zum Umgang mit diktatorischer Vergangenheit’, in: K. Hammerstein et al. (eds), Aufarbeitung der Diktatur – Diktat der Aufarbeitung? Normierungsprozesse beim Umgang mit diktatorischer Vergangenheit (Gottingen, 2009), pp. 189-203; K. Hammerstein, ‘Europa und seine bedruckende Erbschaft. Europaische Perspektiven auf die Aufarbeitung von Diktaturen’, in: Werner Reimers Stiftung (ed.), Erinnerung und Gesellschaft. Formen der Aufarbeitung von Diktaturen, Berlin (forthcoming).

9. Cf. essentially W. von Scheliha, ‘Der Pakt und seine Falscher. Der geschichtspolitische Machtkampf in Russland zum 70. Jahrestag des Hitler-Stalin-Pakts’ (in this volume) and id., ‘Die List der geschichtspolitischen Vernunft. Der polnischrussische Geschichtsdiskurs in den Gedenkjahren 2009-2010’, in: E. Francois, R. Traba and S. Troebst (eds), Strategien der Geschichtspolitik in Europa seit 1989 – Deutschland, Frankreich und Polen im internationalen Vergleich, Gottingen (forthcoming). See also T. Timofeeva, ‘“Ob gut, ob schlecht, das ist Geschichte”. Russlands Umgang mit dem Hitler- Stalin-Pakt’, Osteuropa 59 (2009) 7-8, pp. 257-271, and Jutta Scherrer’s contribution to this volume.

10. On this cf. the contributions of A. Bubnys, K. Wezel and K. Bruggemann in this volume.

11. Council of Europe, Parliamentary Assembly: Resolution 1096 (1996) on measures to dismantle the heritage of former communist totalitarian regimes. Strasbourg, 27 June 1996, assembly.coe.int, accessed 01.06.2011.

12. Council of Europe, Parliamentary Assembly: Motion for a Resolution on the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, presented by Mr Paunescu, Romania, UEL, and others. Strasbourg, 12 July 1995 (Doc. 7358), assembly.coe.int, accessed 01.06.2011.

13. European Parliament resolution on remembrance of the Holocaust, antisemitism and racism. Brussels, 27 January 2005, www.europarl.europa.eu, accessed 01.06.2011. For the background cf. H. Schmid, ‘Europaisierung des Auschwitz- Gedenkens? Zum Aufstieg des 27. Januar 1945 als “Holocaustgedenktag” in Europa’, in: J. Eckel and C. Moisel (eds), Universalisierung des Holocaust? Erinnerungskultur und Geschichtspolitik in internationaler Perspektive (Gottingen, 2008), pp. 174-202; Jens Kroh, Transnationale Erinnerung. Der Holocaust im Fokus geschichtspolitischer Initiativen (Frankfurt a. M./ New York, 2008); D. Levy and N. Sznaider, Erinnerung im globalen Zeitalter: Der Holocaust (Frankfurt a. M., 2001), pp. 210-216.

14. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on the Holocaust Remembrance (A/RES/60/7, 1 November 2005), www.un.org, accessed 01.06.2011.

15. European Parliament, plenary debates. Strasbourg European Parliament. Plenary debates. Strasbourg, 11 May 2005, www.europarl.europa.eu, accessed 01.06.2011.

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.

18. European Parliament resolution on the sixtieth anniversary of the end of the Second World War in Europe on 8 May 1945. Strasbourg, 12 May 2005, www.europarl.europa.eu, accessed 01.06.2011.

19. Putin o pakte Molotova-Ribbentropa: ‘Chorošo ėto bylo ili plocho – ėto istorija’, Regnum. Informacionnoe agentstvo (10.05.2005), http://www.regnum.ru/news/451397.html, accessed 29.06.2011. On this see also Jutta Scherrer’s contribution in this volume.

20. European Parliament. Plenary debates. Tuesday, 4 July 2006 – Strasbourg: 70 years after General Franco’s coup d’etat in Spain, www.europarl.europa.eu, accessed 01.06.2011.

21. Ibid. (Speech of the Social Democrat Martin Schulz.) The debate took place in the context of the ‘Recommendation 1736 (2006) Need for international condemnation of the Franco regime’, passed by the European Council on 17 March 2006. This had given Spain’s government detailed recommendations for dealing with the memory of the legacy of the Franco dictatorship of 1939 to 1975. Cf. Council of Europe, Parliamentary Assembly: Recommendation 1736 (2006) Need for international condemnation of the Franco regime. Strasbourg, 17 March 2006, http://assembly.coe.int/main.asp?Link=/documents/adoptedtext/ta06/erec1736.htm accessed 01.06.2011; K. Hammerstein and B. Hofmann, ‘Europaische ‘Interventionen’’, pp. 194-196. On the structural parallels of strategies for dealing with the past of the late and post-dictatorial periods between Southern Europe and Central and Eastern Europe see S. Troebst, Diktaturerinnerung und Geschichtskultur im östlichen und südlichen Europa. Ein Vergleich der Vergleiche (Leipzig: Leipziger Universitatsverlag, 2010), www.uni-leipzig.de/gesi/documents/working_papers/GESI_WP_3_Troebst.pdf, accessed 30.06.2011.

22. On this subject cf. B. Hofmann, ‘Europaisierung der Totalitarismustheorie? Geschichtspolitische Kontroversen um das ‘Schwarzbuch des Kommunismus’ und die Europaratsresolution zur ‘Verurteilung der Verbrechen totalitarer kommunistischer Regime’ in Deutschland und Frankreich’, in: id. et al. (eds), Diktaturüberwindung in Europa. Neue nationale und transnationale Perspektiven (Heidelberg, 2010), pp. 331-347; K. Hammerstein and B. Hofmann, ‘Europaische “Interventionen”’, pp. 196-202.

23. Council of Europe, Parliamentary Assembly: Resolution 1481 (2006) Need for international condemnation of crimes of totalitarian communist regimes. Strasbourg, 25 January 2006, assembly.coe.int, accessed 01.06.2011.

24. The Slovenian EU Presidency of the EU Council thus held a hearing on 8 April 2008 in Brussels, primarily with the participation of experts from Central and Eastern Europe, on the crimes of the totalitarian regimes, with communist state crimes being of central concern. On this cf. the comprehensive report by von Peter Jambrek (ed.), Crimes Committed by Totalitarian Regimes. Ljubljana 2008, 316 pp. www.mp.gov.si, accessed 01.06.2011.

25. Prague Declaration on European Conscience and Communism. Prague, 3 July 2008, www.praguedeclaration.org, accessed 01.06.2011.

26. K. Hammerstein and B. Hofmann, ‘Europaische “Interventionen”’, p. 196. See also F. Wenninger and J. Pfeffer, ‘Total normal. Zur diskursiven Durchsetzung des Totalitarismus-Begriffs in Debatten des Europaischen Parlamentes’, Conference Papers, Momentum-Kongress 2010 (Hallstatt, 21.-24.10.2010) (forthcoming). However, even the influential Copenhagen document of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe of 1990, passed at the climax of the euphoria over the collapse of communism in 1990, stated ‘The participating States clearly and unequivocally condemn totalitarianism’. Cf. Document of the Copenhagen Meeting of the Conference on the Human Dimension of the CSCE (Copenhagen, 29 June 1990), Point 40, http://www.osce.org/odihr/19394, accessed 01.06.2011.

27. Declaration of the European Parliament on the proclamation of 23 August as European Day of Remembrance for Victims of Stalinism and Nazism. Brussels, 23 September 2008, www.europarl.europa.eu, accessed 01.06.2011.

28. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: 23 August: International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and of its Abolition, portal.unesco.org, accessed 01.06.2011.