Powody, dla których pamiętamy są tak zróżnicowane jak osoby i konstelacje, w których dochodzi do przywołania wspomnień, ich konserwowania czy też przekazywania innym. Przy wszelkiej różnorodności form pamięci, odbywa się to zwykle w obrębie przyjętych przez daną wspólnotę lub państwo odniesień, w ramach których dochodzi do wymiany doświadczeń i pielęgnowania pamięci. Pamięć zbiorowa selekcjonuje, zachowuje i przekazuje zdarzenia i procesy w postaci spuścizny i tradycji nacechowanej przede wszystkim przez narodowe konotacje.

XIX wiek przebiegał pod znakiem narodowych przebudzeń, których liberalna wolnościowe treści w drugiej połowie stulecia sukcesywnie zamieniały się w agresywny, często ksenofobiczny konserwatyzm, który trafnie opisuje Heinrich August Winkler jako przemianę „lewicowego w prawicowy nacjonalizm”. W XX wieku widoczne są przyśpieszona dynamika wydarzeń, erozja tradycyjnych wartości oraz zmierzające do totalitaryzmu nacjonalizmy, które w sposób trwały wstrząsnęły europejskim porządkiem. Synonimami tego co nowe i niemierzalne w XX wieku stały się pojęcia, takie jak przemoc, wojna totalna, Holokaust, nazizm, komunizm i wypędzenia, aby wymienić tylko kilka z nich.[1]

Nowością XX wieku nie były same w sobie dążenia hegemonistyczne dużych mocarstw, lecz niszczycielski impet bolszewickiej rewolucji z jej globalnymi implikacjami oraz bezprecendensowość rozpętanej i prowadzonej w sposób totalny przez nazistowskie Niemcy II wojny światowej. Tym razem państwa europejskie nie były w stanie własnymi siłami, tak jak to miało miejsce w poprzednich stuleciach, odeprzeć naznaczonego rasizmem obłędu podbojów i osiągnąć samodzielnie określonej europejskiej równowagi. Wyzwolenie od nazizmu przyszło z zewnątrz, z azjatyckiej części Związku Radzieckiego i zza Atlantyku. Ceną była akceptacja wynegocjowanego w Jałcie, a notyfikowanego w Poczdamie podziału Europy, przy czym jego konsekwencje były znacznie poważniejsze i bardziej bolesne dla państw na wschód od Łaby, niż dla tych na Zachodzie: utrata wolności, ograniczenie państwowej suwerenności, jak również szans życiowych pojedynczych osób, poprzez stworzenie porządku państwowego na wzór sowiecki.[2]

*

W Europie Zachodniej proces historyczny przebiegał inaczej. Tu, Stany Zjednoczone przejęły funkcję wzorca, liberalna demokracja parlamentarna zwyciężyła w większości krajów. Co zresztą, w znacznym stopniu związane było z pouczającym doświadczenie zagrożeń dla demokracji wyniesionym wobec okresu międzywojennego oraz z łatwym do zapamiętania negatywnym kontrastem z dyktatorskiego „bloku wschodniego”. Do tego doszła dwudziestoletnia dobra koniunktura w gospodarce światowej, generująca stabilność i dobrobyt na Zachodzie, co doprowadziło do powolnego, ale stałego wyobcowania się wschodniej części kontynentu. Skuteczna ekonomiczna i polityczna integracja Europy Zachodniej również miała istotne znaczenie dla treści, którymi elity i społeczeństwa wypełniały wyobrażenia o Europie.[3]

Jeżeli mówiono o Europie, to od lat sześćdziesiątych XX wieku w Paryżu, Bonn czy Brukseli było oczywistym, że ma się na myśli Europę Zachodnią. Ponadto, region między Renem, Mozą a Mozelą, jako centrum administracyjne i gospodarcze WE, postrzegał już nawet Skandynawię i Morze Śródziemne jako obszary peryferyjne. Zaś wschodnia część Europy funkcjonowała w wyobrażeniach większości zachodnich Europejczyków jako szary jednolity blok lub ginęła z ich świadomości. Zachodni Europejczycy widzieli siebie samych jako przedstawicieli tej ‚właściwej’ Europy, nie zauważając już po jakimś czasie nawet braku tej drugiej połowy. Tylko niewielu podnosiło przed upadkiem muru problem braku Wschodu w zachodniej świadomości.[4]

O tym, że podział kontynentu na Wschód i Zachód, na totalitarne/autorytarne i demokratyczne systemy nie był ‚naturalnym wynikiem’ II wojny światowej, świadczą projekty federacyjne na czasy po upragnionym zwycięstwie nad Trzecią Rzeszą, powstające grupy oporu wszędzie w Europie. Ernst Friedländer mówi nawet o „narodzinach europejskiego federalizmu z ducha ruchu oporu“.[5] Nauka, jaką należało wyciągnąć z rażącej porażki Ligi Narodów oraz z niszczących nacjonalizmów - a w szczególności nazizmu - była jedna, a było nią europejskie zjednoczenie. Ważne dokumenty poświadczające wolę odnowy, jak „Manifest z Buchenwald” opatrzone były w sposób oczywisty podpisami wschodnich i zachodnich Europejczyków. Gdy w maju 1948 roku na „Kongresie Europejskim“ w Hadze spotkało się ponad 600 przedstawicieli europejskich narodów nie brakowało przed budynkiem obrad flag państw Wschodnioeuropejskich. Jednakże wówczas kraje te reprezentowali jedynie uchodźcy. W październiku 1948 roku na Światowym Kongresie Intelektualistów w Obronie Pokoju we Wrocławiu obecni byli wprawdzie zachodni przedstawiciele,[6] ale strona sowiecka pracowała przez cały czas nad ideologicznym podziałem kontynentu.[7]

Odtąd groziło wschodniej połowie kontynentu jako takiej oraz intelektualnemu wkładowi jej reprezentantów w europejskie plany federacyjne zapomnienie i zapewne zniknąłby całkowicie z pola widzenia zachodnioeuropejskiej opinii publicznej, gdyby nie uchodźcy. To oni w okresie zimnej wojny próbowali, indywidualnie oraz przez zakładane czasopisma i koła, nie dopuścić do tego, aby wschodnie doświadczenia poszły w zapomnienie. Do ośrodków literatury i publicystyki na uchodźstwie należały: dla Czechosłowacji wydawnictwo „Sixty-Eight Publishers Corporation“ z siedzibą w Toronto oraz „ Wolna Agencja Prasowa” w Wurmannsquick,[8] dla Węgier wydawane w ostatnich czasach w Monachium czasopisma Új Látóhatar und Nemzetőr oraz politycznie miarodajny, ukazujący się w języku niemieckim Europäische Rundschau z Wiednia.[9] Dla Polski znaczący wpływ w środowisku literatów oraz politycznych emigrantów uzyskało, ukazujące się pod Paryżem czasopismo Kultura, które inspirowało intelektualny dyskurs oraz środowisko opozycjonistów w kraju.[10]

Przeciwko politycznemu podziałowi Europy, a co było jeszcze gorsze, przeciwko przyzwyczajaniu się i kulturowej akceptacji tego podziału przez zachodnich Europejczyków wypowiadały się dziesiątki intelektualistów i dysydentów z Europy środkowowschodniej. To słynny esej, żyjącego na emigracji, Milana Kundery Un Occident kidnappé czyli Tragedia Europy Centralnej jak i książka Antypolityka węgierskiego socjologa György Konrada wywołały w połowie lat 80. debatę na temat Europy Środkowej. Kundera konstatuje przesunięcie po 1945 roku o kilkaset kilometrów na zachód starych granic pomiędzy katolicyzmem a prawosławiem, tak że geograficzne centrum Europy znalazło się obecnie kulturowo na Zachodzie, a politycznie na Wschodzie.[11] Konrad traktował „Antypolitykę“ jako sposób przeciwstawienia się temu arbitralnemu podziałowi. Społeczeństwa poddane naciskom totalitarnego państwa muszą - jego zdaniem - nauczyć się prowadzić własne życie, rozwijając liczne formy współpracy i jednoczenia się, aby w ten sposób, krok po kroku, zbudować ponad granicami społeczeństwo obywatelskie.[12]

Podczas, gdy węgierscy i czechosłowaccy autorzy skłaniali się ku debatom na temat ich samoświadomości i poziomu cywilizacji w odniesieniu do Rosji/Związku Radzieckiego, w polskich dyskusjach o Europie Środkowej przeważały tematy, takie jak stosunek do obu państw niemieckich i Związku Radzieckiego. Zresztą geograficzne położenie Polski skłaniało wręcz do wyjaśnienia swoich stosunków z sąsiadami.[13] Swoim głosem w debacie o Europie Środkowej intelektualiści z „bloku wschodniego“ zwrócili uwagę na braki w postrzeganiu Europy Zachodniej oraz podkreślili swoją europejską tożsamość.[14]

Jak się wydaje, najtrwalej oddziaływał ponad 40-letni polityczny podział kontynentu na Wschód i Zachód, na autorytarne/totalitarne i demokratyczne systemy. Przypadek, że człowiek rodził lub znajdował się pod tą lub inną formą rządów, miał dla niego poważne, a czasem wręcz zagrażające jego życiu konsekwencje, zwłaszcza kiedy trzeba było odróżnić prawdę od kłamstwa i chciało się to bez obaw wypowiedzieć. Polski poeta Czesław Miłosz po ucieczce na Zachód w 1951 roku, opisuje w swoim eseju Zniewolony umysł, który ukazał się 2 lata później, zachowania intelektualistów w stalinizmie, nacechowane strachem, uległością ale również lojalnością w stosunku do władzy. Karl Jaspers docenił starania późniejszego laureata Nagrody Nobla w następujący sposób:

Miłosz nie pisze jak nawrócony komunista, nie odczuwa się u niego owego agresywnego fanatyzmu wolności, który wyczuwalny jest w gestach, tonie i działaniach jako odwrócenie totalitaryzmu. Nie pisze on jak opozycjonista na emigracji, który praktycznie myśli o przewrocie i powrocie. Mówi jako wstrząśnięty człowiek, który z wolą sprawiedliwości i niezniekształconej prawdy poprzez analizę zdarzeń dziejących się w terrorze ukazuje siebie samego.[15]

Znajomość Wschodu i Zachodu przez Miłosza, jego wrażliwość oraz zdolność do empatii wyróżniały go wówczas od uległych wobec władzy na Wschodzie, jak i od licznych intelektualistów na Zachodzie, którzy traktowali obalenie nazizmu jako zasługę Związku Radzieckiego i nie widzieli, względnie nie chcieli widzieć, Janusowego oblicza komunizmu z jego immanentną przemocą i ideologicznym zawłaszczeniem. Zdolność do zrozumienie i empatii udowodnił Miłosz w swojej późniejszej twórczości, co nie zawsze było oczywiste po zakończeniu konfrontacji miedzy blokami w 1989 roku. Obserwujemy podzieloną pomiędzy wschodnią a zachodnią Europę pamięć, tylko że linie podziałów przebiegają obecnie przez ekonomicznie i politycznie rozszerzoną Unię Europejską.[16]

*

Aktualność i siła wybuchowa podzielonej europejskiej pamięci ukazały się na początku XXI wieku po rozszerzeniu Unii Europejskiej. W dalszej części postaram się pokazać, na przykładzie podejścia do nazizmu i komunizmu, szczególnie odnosząc się do tematu wypędzeń, ambiwalencje i rysy w krajobrazie europejskiej pamięci.

Doświadczenia wypędzeń wpisanją się w europejski kontekst XX wieku, ale wspominamy je nie jako europejskie, lecz z reguły jako narodowe doświadczenia. Pamięć o ucieczkach i wypędzeniach, w zależności od kraju i pokolenia, utrwalała własne obrazy, które z kolei mogły być wspierane lub wypierane przez władze i z tego też względu ulegały znacznym zmianom. Nic w tym zresztą dziwnego, ponieważ w pierwszym rzędzie pamiętamy o tym, co sami przeżyliśmy, widzieliśmy lub słyszeliśmy. Perspektywa doświadczeń bezpośrednich może w pokoleniu, które ich doznało prowadzić do odizolowanego postrzegania wielkich historycznych wydarzeń, które dla potomnych są ze sobą związane. Indywidualna pamięć nierzadko przebiega na skos do wielkich wydarzeń historycznych, a mimo to - a może właśnie dlatego - jest tak ważna. To właśnie w niej zakodowane są dialekty, krajobrazy, zwyczaje, a nawet zapachy i to ona jednocześnie podlega z biegiem lat zmianom. Strach i niepewność mogą w takim samym stopniu, jak zdolność do autorefleksji lub nawet autokorekty, wpływać na indywidualną pamięć. Szczególną wartość indywidualnej pamięci przedstawia jej autentyczność, ale ze względu na swoją emocjonalność jest łatwa do podważenia. Tej sprzeczności nie można rozwiązać, ale można nad nią zapanować, postrzegając losy ludzi z innych krajów z empatią i zdając sobie z tego sprawę, że doświadczenia przesiedleń i wypędzeń – niezależnie, czy dotyczą Polaków, Ukraińców czy Niemców – były dla jednostki tak samo bolesne. Pamięć zbiorowa dotycząca wypędzeń, włączająca również wtórne, nie będące wynikiem bezpośrednich przeżyć wspomnienia, nie może uciec od wrażliwości moralnej w odniesieniu do okrutnych czynów swoich rodaków i refleksji nad przyczynami i skutkami wypędzeń. Dopiero wówczas pamięć zbiorowa zaczyna różnić się od prostej sumy pojedynczych doświadczeń i możemy ją faktycznie odróżnić od pamięci indywidualnej.

Rozróżnienie to opiera się na prawie weta osobistej pamięci wobec jakiejkolwiek próby włączania jej do zbioru pamięci. Według Reinharta Kosellecka należy to „do tyleż często co na próżno przywoływanej godności człowieka, który ma prawo do własnej pamięci”. Koselleck doradza ostrożność przed nadminnym posługiwanem się terminem „zbiorowej pamięci”:

Nie ma zbiorowej pamięci, są jednak zbiorowe warunki możliwych pamięci. Tak jak zawsze istnieją ponadindywidualne warunki i przesłanki dla własnych doświadczeń, tak samo istnieją społeczne, mentalne, religijne, polityczne, wyznaniowe warunki – oczywiście też narodowe – dla różnych możliwych pamięci. Działają one niczym śluzy filtrujące osobiste doświadczenia w taki sposób, że utrwalają się te, które można łatwo odróżnić. Uwarunkowania polityczne, społeczne, wyznaniowe lub inne ograniczają więc pamięć, a jednocześnie ją uwalniają.[17]

Wobec trudności znalezienia właściwej formy pamięci i jej możliwej korekty powstaje pytanie: Jaką rolę może odegrać historia jako nauka opisująca wydarzenia historyczne? Hans Günter Hockerts zasugerował pojęciową triadę „doświadczenia pierwotne, kultura pamięci i nauki historyczne” jako typologię dostępu do historii współczesnej. Przy czym, doświadczenia pierwotne rozumiane są, jako dzieje doświadczone osobiście, kultura pamięci zaś jako suma publicznego, nie specyficznie naukowego posługiwania się historią, przy użyciu różnych środków i w najrozmaitszych celach. To, że historia jest instrumentalizowana i zaspakajać ma potrzeby rozrywki informacyjnej (infotainment) zauważalne jest szczególnie w przypadku historii współczesnej. Interwencje i próby sprostowań podejmowane przez naukowców szybko natrafiają tu na ograniczenia.[18]

Elementem konstytuującym naukę są stworzone przez nią standardy „systematycznego, opartego na regułach i dającego się sprawdzić procesu pozyskiwania wiedzy“. Jest ona świadoma uzależnienia wiedzy historycznej od miejsca i ujawnia mniej lub bardziej otwarcie obowiązujące ją założenia. Spornymi były i pozostają jednak przyporządkowanie faktów, ich waga i powiązania, zwłaszcza, że trudno o nich rozstrzygnąć na podstawie czysto naukowych kryteriów. Tu, znajduje właściwe sobie miejsce podejście wieloperspektywiczne. Bo, nie o regularnie pożądany „obiektywizm” tu chodzi, ponieważ nie ma stałego punktu odniesienia dla jego sprawdzenia. Musi jednak istnieć, jako metoda kontroli i korekty, możliwość intersubiektywnego sprawdzenia w dyskursie naukowym. „Różnorodność pamięci nie oznacza, że ogłaszamy wszystko jako dozwolone. Specjalistyczne kompetencje mogą przyczynić się do tego, że pluralizm nie popadnie w dowolność“ i pomoże zdecydowanie przeciwstawić się legendom.[19]

Nawet jeżeli powstają metodologiczne wątpliwości, czy zasadne jest scharakteryzowanie XX wieku, jako „wieku wypędzeń”, to nie można jednak zaprzeczyć dużej ilości wymuszonych migracji w pierwszej połowie ubiegłego stulecia. Jako przykłady można wymienić tu, między innymi wypędzenie Ormian z Turcji w 1915 roku, grecko-turecką „wymianę ludności” z 1922 roku, wypędzenie Polaków przez niemieckiego najeźdźcę w 1939 roku, deportację Czeczenów i Inguszów w 1944 roku, wypędzenie Niemców ze wschodniej części Europy w latach1945-1948, oraz tak zwane czystki etniczne w byłej Jugosławii w latach 1991-1999. Wszystkie te przymusowe migracje łączyło to, że były skierowane przeciwko grupom etnicznym, które przez mobilizację negatywnych narodowych uczuć i ukierunkowaną propagandę można było oddzielić jako obce i niebezpieczne. Posługiwano się domniemanym lub faktycznym nielojalnym zachowaniem danej grupy etnicznej w stosunku do państwa lub innych grup ludności, jako powodem dla przymusowych migracji i uzasadniano je w ten sposób politycznie. Wypędzeniom z reguły towarzyszyły zbiorowe pozbawianie praw, brutalna przemoc oraz poniżanie jednostek, proces nie raz nabierał nieludzkiej dynamiki i zachodził dużo dalej, obciążając dotknięte grupy bardziej, niż to co polityczni decydenci definiowali jako „humanitarny i uporządkowany transfer ludności”.[20]

Obok wspólnych cech wtnieją też zasadnicze różnice między wymienionymi przymusowymi migracjami. Mogły to być motywy etniczne, polityczne, ideologiczne lub rasowe, podyktowane sprawami wewnętrznymi kraju lub oddziaływać na zewnątrz. W pierwszym 30-leciu XX wieku wypędzenia na kontynencie wychodziły z wewnątrz jakiegoś państwa i tak jak w przypadku grecko-tureckiego konfliktu Traktatem z Lozanny w 1923 roku zotało chociaż ex post usankcjonowane pod kątem prawa międzynarodowego. W tym konkretnym przypadku chodziło o polityczne rozbrojenie grecko-tureckiego konfliktu, nawet jeżeli ten rodzaj rozwiązań odbywał się kosztem dotkniętych nim grup, niósł ze sobą utratę ojczyzny oraz pozostawiał za sobą straumatyzowanych i zabitych.

Wraz z II wojną światową wypędzenia znacznie zmieniły swój charakter. Naziści po napaści na Polskę posłużyły się po raz pierwszy wypędzeniami, jako środkiem niepohamowanej polityki podbojów, przesuwając na mapie grupy ludności, bez pytania ich o zdanie, jak tzw. Volksdeutsche, okradając z ojczyzny miliony Polaków, Rosjan, Ukraińców i Czechów oraz systematycznie mordując Żydów. Gdyby nie nazizm ze swoją brutalną polityką przesiedleńczą i zagłady we Wschodniej Europie nie doszłoby do wypędzeń Niemców po 1945 roku. Nazistowskie Niemcy były tym krajem, który posłużył się wypędzeniami dla realizacji swojej agresywnej polityki zdobywania przestrzeni życiowej (Lebensraum) i tym samym wprowadził fatalny wzorzec postępowania do Europy, który szczególnie wykorzystał Stalin.[21]

Podczas gdy naziści wypędzali i mordowali z powodów rasowych i związanych z polityką osadnictwa, bolszewicy robili to samo z pobudek ideologicznych i wewnątrzpolitycznych. Zaś imperialne ambicje i utopijne fantazje o czystości etnicznej były tym, co łączyło „Trzecią Rzeszę“ i Związek Radziecki, jak stwierdził Jörg Baberowski. ZSRR był państwem wielonarodowym, dopóki bolszewicy nie rozpoczęli porządkować go na nowo według własnych wyobrażeń. „Trzecia Rzesza” była państwem narodowym, które w następstwie zbrojnej ekspancji przemieniło się w wielonarodowe imperium. „Dopiero przyswajało sobie ową ambiwalencję, której nie mogli znieść jej przywódcy. Oba reżimy, nazizm i bolszewizm, potęgowały chaos, którego chcieli pozbyć się za pomocą swoich projektów porządku. Gdy dostrzegli nie tylko obcą rzeczywistość, lecz także zagrożenie dla społecznych projektów, które ze sobą przynieśli. Dlatego też zdobywcy poznali świat poza znajomym porządkiem jedynie jako wrogi kontrprojekt.“[22]

Naziści i bolszewicy doświadczyli I wojnę światową i następującą po niej wojnę domową jako walki toczące się w wielonarodowym i pełnym przemocy kontekście. Podczas gdy jedni wykrywali „barbarzyńców“ i „podludzi“, drudzy widzieli „zdrajców“ i „wrogów“, których ucieleśnieniem były rasy i narody. Te doświadczenia były znaczące dla tworzenia się nazistowskich i bolszewickich programów porządku i fantazji związanych z czystkami etnicznymi.[23]

„Nazistowski reżim okupacyjny na Ukrainie, Białorusi i krajach bałtyckich zmienił od 1941 roku nie tylko etniczną mapę Związku Radzieckiego, ale również samoocenę dotkniętych grup narodowych oraz myślenie bolszewików o imperium. Odtąd Żydzi byli tylko Żydami, Niemcy tylko Niemcami i Czeczeńcy tylko Czeczenami. To, kim jeszcze byli, utraciło dla wszystkich stron po doświadczeniach II wojny światowej znaczenie. W czasie wojny bolszewicka retoryka dotycząca wroga nabrała cech etnicznych i biologicznych, była odpowiedzią na insynuacje, które wnieśli do Związku Radzieckiego naziści. Bez podboju i eksploatacji obcych ziem, które zamieszkiwali wrogowie, naziści i bolszewicy nie mogliby rozpętać totalnej wojny przeciwko wewnętrznym i zewnętrznym wrogom. Dlatego też imperium było historycznym miejscem totalitarnego projektu porządku.“[24]

Biorąc pod uwagę ciąg przyczynowo-skutkowy oraz naszkicowaną powyżej dynamikę woli do tworzenia porządku i wypędzeń, używanie pojęcia ‚stulecie wypędzeń’ jest problematyczne. Przy ukierunkowaniu na longue durée istnieje niebezpieczeństwo prostego chronologicznego uszeregowania wypędzeń – zaczynając od wypędzeń i mordu Ormian w 1915 roku, a kończąc na etnicznych czystkach w Jugosławii w latach 90. XX wieku. Takie ilościowe podejście jednak niewiele wyjaśnia, sugeruje wręcz związek między poszczególnymi zdarzeniami, który nie istnieje i konstruuje informację zrównującą wypędzenia, jako godne potępienia czyny zasługujące na odrzucenie w takim samym stopniu. Przyczyny poszczególnych wypędzeń etniczne, polityczne, ideologiczne czy też rasowe przy tak generalizującym podejściu pozostają w cieniu. Konieczna wydaje się zaś, obok uświadomienia sobie istniejącej tutaj projekcji porządku, rekonstrukcja kontekstów i horyzontów, w jakich rozgrywały się nierzadko pełne cierpień akty wypędzeń.[25]

Ponadto przymusowe migracje nie były fenomenem, który dotknął całą Europę w XX wieku – były one przede wszystkim środkiem polityki stosowanym we Wschodniej Europie. Holm Sundhaussen pisał o przymusowych migracjach w Europie Południowej, które związane były ze strukturalnym współdziałaniem dwóch czynników, kombinacji centralistycznego, francuskiego modelu państwa z kulturowym modelem „niemieckim”, czy środkowoeuropejskim opartym na pochodzeniu.[26] Philipp Ther przeniósł ten opis stanu rzeczy na państwa Europy Środkowej i Wschodniej. Z wielojęzycznych rzesz, trzymających się razem głównie z powodu politycznych wartości, narodów Rzeszy rozwinęły się w drugiej połowie XIX i wczesnych latach XX wieku państwa narodowe, wymagające od swoich obywateli wyższego stopnia identyfikacji. Przymus do jednoznacznego określenia się w wielonarodowych społeczeństwach znajdował swój wyraz, np. podczas spisów powszechnych, gdzie ludzie musieli zdecydować się na konkretną narodowość.[27]

W okresie międzywojennym przymus jednoznaczności na próbę wystawił ochronę mniejszości, jako zasadniczo chwalebną zasadę kształtowania międzynarodowej polityki,. Podczas konfliktów wkraczała Liga Narodów i ustalała, przykładowo podczas sporu o szkoły na Górnym Śląsku, kto był Niemcem, a kto Polakiem.[28] Stworzony po I wojnie światowej porządek oparty na państwach narodowych spowodował, również na płaszczyźnie międzynarodowej, sytuację, w której naprzeciwko sobie stanęły zdefiniowane na podstawie rzekomo obiektywnych kryteriów narody i mniejszości narodowe. Gdy zaostrzyły się napięcia społeczne w okresie światowego kryzysu gospodarczego, ta etniczna zasada struktury społeczeństwa przyniosła fatalne skutki dla mniejszości narodowych we wschodniej części Europy.

*

Wspomnienia wypełnionego przemocą XX wieku oraz II wojny światowej, która zasadniczo zmieniła mapę Europy, stały się po rewolucji z 1989 roku bardziej wyraziste. To, co w ekonomii od dłuższego czasu, a w polityce od rozszerzenia UE na Wschód opisywane jest słowem homogenizacja, nie odnosi się do zbiorowej pamięci europejskich narodów. Dla zjednoczonej przed końcem sowieckiego imperium Europy (Zachodniej) Auschwitz stał się wspólnym, negatywnym punktem odniesienia dla ludności krajów Europy Wschodniej ten moment nie stanowił ośrodka ich tożsamości. Pojawiają się dwie historie ofiar, które w zdający się nie do rozwiązania niepokojący sposób konkurują ze sobą: Holokaust i gułag, nazizm i stalinizm.[29]

Geograficznie Polska i Niemcy znajdują się na linii podziału pomiędzy tymi dwiema kulturami pamięci i jednocześnie, jak żaden inny kraj na kontynencie, doświadczyły obu dyktatur, a w przypadku Niemiec również podziału. Od zakończenia wojny Polakom i Niemcom chodziło i nadal chodzi o to, jak umiejscowić „Trzecią Rzeszę” i II wojny światowej we własniej narodowej narracji historycznej. Jest to proces, który stale się powtarza i zależnie od aktualnych potrzeb i stanowisk zmienia akcenty.

W znacznej mierze dotyczy to obu krajów, ponieważ wielowiekowe sąsiedztwo spowodowało, że historia jednego narodu, przynajmniej w pewnych regionach i okresach, jest jednocześnie częścią historii drugiego narodu. Nawet jeżeli te sploty nie kształtowały się symetrycznie, jeżeli Polacy częściej stykali się z niemiecką polityką i kulturą niż na odwrót, wydawać się mogło, że upadek komunizmu stwarzał możliwość przyjrzenia się, już bez żadnych uprzedzeń, niemieckiej i polskiej pamięci i znalezienia ich wspólnych punktów. Przełomowy rok 1989 rozszerzył pole dla kultury pamięci o historię dyktatury komunistycznej spod znaku SED i PZPR.[30]

Historycy obu krajów nawiązujący do polsko-zachodnioniemieckich ustaleń dot. podręczników, teraz już bez politycznych ograniczeń, sprostali tym oczekiwaniom. Okazały się one jednak jako przedwczesne, biorąc pod uwagę nastawienie niemieckiej i polskiej opinii publicznej. Stworzenie nowej, odnoszącej się do własnej historii kultury pamięci miało pierwszeństwo. Po zachodniej stronie Odry i Nysy najważniejszym było “zbadanie historii i skutków dyktatury SED“, zadanie takie oraz nazwę otrzymała komisja śledcza Bundestagu, która otwierając akta Stasi odpowiedziała na elementarne prawo wschodnich Niemców do samostanowienia w kwestiach informacji, a jednocześnie zaspokoiła medialne, „demaskatorskie” zainteresowanie zachodnioniemieckiej opinii publicznej. W Polsce nie było czegoś podobnego.

O ile uporanie się z drugą niemiecką dyktaturą było w uzasadniony sposób wschodnioniemieckim problemem, o tyle faryzeuszostwem była szeroko rozpowszechniona opinia, że jest to zadanie tylko dla obywateli nowych landów, coś w rodzaju ćwiczenia obowiązkowego, aby mogli oczyścić się i stać demokratami, którymi ponoć już byli zachodni Niemcy. Przypadek, że ktoś dorastał na zachód od Łaby i Werry nie czynił go odpornym na codzienne ludzkie słabości – tchórzostwo, zdradę i żądzę władzy. Niemcy żyjący w demokracji mieli to szczęście, że konsekwencje ich zachowań w „Trzeciej Rzeszy” nie egzekwowano tak drastycznie, jak domagał się tego system komunistyczny od mieszkańców byłej NRD w postaci czterdziestoletniej indoktrynacji. Polityczna „wina” niemieckiej przeszłości, jak określiła to politolog Gesine Schwan, „ polega na, w obu częściach kraju nadal nie przezwyciężonej tradycji niedoceniania wolności i tolerancji jako centralnych filarów demokracji względnie redukowania ich istotnych składników “.[31]

Naukowo pożyteczne okazały się, rozpoczęte w latach 90., badania porównawcze nad dyktaturą nazistowską i komunistyczną. Nie chodziło o zrównanie obu systemów lub zrelatywizowanie niszczycielskiej wojny o charakterze rasowym prowadzonej przez nazistów, lecz o strukturalne ujęcie i przeanalizowanie różnic, podobieństw i ewentualnych elementów wspólnych dla obu niemieckich dyktatur, aby wyłuskać specyfikę obu systemów, ale też aby odnaleźć możliwą ciągłość kulturowych wzorców i sposobów zachowań. Wyniki tych studiów porównawczych są merytorycznie znaczące i metodologicznie przekonujące i mogą posłużyć jako podstawa do dalszych badań nad europejskimi dyktaturami XX wieku.[32]

*

Sytuacja w Polsce po 1989 roku charakteryzowała się tym, że najwidoczniej nie istniała potrzeba zajmowania się podzieloną przeszłością, ze wszystkimi towarzyszącymi jej medialnymi zjawiskami. Podobnie jednak jak w nowych krajach związkowych, trzeba było opracować kryteria podejścia do dyktatorskiej przeszłości i to znajdując się w stanie mentalnym, który wprawdzie nie pod względem treści, ale pod względem struktur był w znacznym stopniu uformowany przez system, z którym teraz miano się rozprawić. Pierwszy, wybrany w wolnych wyborach rząd w „bloku wschodnim” z premierem Tadeuszem Mazowieckim unikał rozrachunku z komunistyczną przeszłością, co było zgodne z wolą większości opinii publicznej w Polsce. Postępowanie to, określane przez nich samych, jako polityka „grubej kreski”, może poprawiło trudne początkowe warunki działania rządu, ale długofalowo okazało się negatywne, gdyż zabrakło w dużej mierze katartycznego podejścia do indywidualnych, obarczonych winą zachowań w czasach dyktatury w Polsce Ludowej.[33]

Stan ten skłaniał w latach 90. do podejrzeń i denuncjacji, które mogły być instrumentalnie wykorzystywane w walce politycznej. A nawet więcej, fakt, że „Trzecia Rzeczpospolita“ nie odcięła się ostentacyjnie od swojej nieprawnej poprzedniczki wpływał na nastawienie obywateli do ich państwa. A wyobrażenie, iż nowe państwo zabezpiecza partykularne interesy starych elit, spotkało się z szerokim odzewem, pozostał sceptycyzm w stosunku do „tych innych“ rządzących.[34]

Kiloński historyk Rudolf Jaworski w połowie lat 90. stwierdził istnienie wręcz przeciwstawnych tendencji w kulturze pamięci w Niemczech i Polsce. Od zjednoczenia Niemiec „widoczny był powrót do świadomości wspólnej niemieckiej historii, zaś w postkomunistycznej Polsce wzrastało znużenie historią”. Otwierające się nowe szanse tworzenia teraźniejszości i przyszłości doprowadziły w Polsce do osłabienia uprzednio niemal obsesyjnego utrwalania swojej przeszłości, zaś Niemcy wręcz odwrotnie, z większą pewnością siebie zwrócili się ku swojej historii, którą wcześniej raczej wypierali lub nawet jej zaprzeczali.[35]

Te trafne dla lat 90. obserwacje utraciły w nowym dziesięcioleciu zwłaszcza dla Polski swoją wiarygodność. Od 2000 roku media i opinia publiczna zaczęły intensywnie zajmować się własną historią. Stało się to za sprawą debaty o Jedwabnem i pytania o udział i współudział Polaków w pogromie ludności żydowskiej w owe miejscowości w 1941 roku. Debata ta była bolesnym i zarazem istotnym kamieniem milowym dla pamięci polskiego społeczeństwa, ponieważ wystawiono na próbę starannie przekazywany martyrologiczny obraz własny wielu Polaków. Zdaniem, uważanej za autorytet moralny publicystki i byłej działaczki Solidarności, Haliny Bortnowskiej skutkiem tej otwartej i emocjonalnie przebiegającej debaty było poddanie w wątpliwość pielęgnowanego, również w czasach Polski Ludowej, obrazu własnego zawsze niewinnych ofiar, który w debacie o Jedwabnem w dramatyczny sposób kolidował z rodzimym antysemityzmem.[36]

*

Pojawił się też nowy punkt zapalny w dyskusji o szczególnym miejscu Holokaustu w europejskiej kulturze pamięci. Był nim koniec konfrontacji między blokami i poniekąd wspólna pamięć Europejczyków ze Wschodu, którzy po dziesiątkach lat indoktrynacji i milczenia pod jarzmem komunizmu mogli wreszcie wyartykułować swoje cierpienia, dla którego szukali zrozumienia również na zachodzie kontynentu. Przykładem, może być przemówienie z 24. marca 2004 roku na Targach Książki w Lipsku ówczesnej łotewskiej Minister Spraw Zagranicznych, a obecnie Komisarza UE, Sandry Kalniete. W swoim wystąpieniu podkreśliła, że po wyzwoleniu z nazistowskiego koszmaru w 1945 roku „w połowie Europy terror nie skończył się i że po drugiej stronie żelaznej kurtyny reżim sowiecki kontynuował prześladowania i zagładę narodów Europy Wschodniej, jak również własnego. Przez 50 lat pisano historię Europy bez nas, jako historię zwycięzców z typowym podziałem na dobro i zło, tych którzy mają rację i tych którzy jej nie mają. Dopiero po upadku żelaznej kurtyny naukowcy otrzymali dostęp do dokumentów archiwalnych i historii ofiar, które potwierdzają, że oba reżimy totalitarne – nazizm i komunizm – były równie zbrodnicze”.[37]

Te ostatnie słowa spowodowały, że, zastępca przewodniczącego Centralnej Rady Żydów w Niemczech, Salomon Korn demonstracyjnie opuścił salę. W wywiadzie dla Leipziger Volkszeitung nazwał zrównywanie zbrodni Związku Radzieckiego z nazistowskimi jako “nie do zniesienia“.[38] Niektórym komentatorom przypominało to niemiecki „spór historyków“ z 1986 roku.[39] Sandrze Kalniete chodziło o zwrócenie uwagi na prawie nieznane na Zachodzie związane z ludobójstwem doświadczenia dwumilionowego narodu łotewskiego, gdzie prawie każda rodzina może opowiedzieć o swych trudach i cierpieniach w systemie gułagu. Dotyczyło to również Sandry Kalniete, która zresztą opisała je w swojej książce Ar balles kurpēm Sibīrijas sniegos.[40]

W Niemczech książka wywołała pochwały jak i gwałtowną krytykę.[41] Za twierdzeniem o rzekomo powszechnej kolaboracji Łotyszy z narodowymi socjalistami kryje się niemiłe uczucie,[42] że twierdzenie o Holocauście jako micie założycielskim (Zachodniej) Europy nie jest akceptowane na „Wschodzie”. Na „Wschodzie” uważany jest podobno przez wiele osób ten - dominujący w „zachodniej” kulturze pamięci - prymat za przejaw arogancji, tym bardziej, że ich własne doświadczenia opiekuńczego komunizmu nie znalazły swojego miejsca w „zachodniej” kulturze pamięci.[43]

Nawet jeżeli obecnie kontynent przezwyciężył politycznie jałtański porządek, ów podział na dyktatorski Wschód i demokratyczny Zachód jako skutek II wojny światowej, to kultury pamięci Europy Wschodniej i Zachodniej funkcjonują nadal obok siebie, a nawet często w opozycji do siebie, tak jakby konieczność życia za żelazną kurtyną zapadła mocniej w pamięci środkowowschodnich Europejczyków, niż uważano to za możliwe w zachodnioeuropejskich stolicach. Skutkuje to tym, że pamięć komunikatywna na Wschodzie i Zachodzie po dwudziestoleciu od rewolucji z 1989 roku wypełniona jest mało kompatybilnymi wspomnieniami i objawia niezrozumienie we wzajemnym postrzeganiu oraz brak wyobraźni na Zachodzie.[44]

Podczas gdy na Zachodzie w życiu publicznym poświęca się pamięci o Holokauście niezmiennie dużą uwagę, wiedza o gułagach ogranicza się do niewielkiej grupy osób i ponadto grozi jej popadnięcie w zapomnienie. Amerykańska publicystka, Anne Applebaum, sformułowała ten dylemat następująco: „[Jeżeli] zapomnimy o gułagu, […] zaczniemy zapominać, o tym co nas mobilizowało i inspirowało, co tak długo cementowało cywilizację, Zachodu. […] Jeżeli nie zainteresujemy się historią drugiej połowy kontynentu europejskiego, historią t.j. drugiego totalitarnego reżimu XX wieku, to w końcu nie będziemy rozumieli własnej przeszłości i nie będziemy wiedzieli, dlaczego nasz świat stał się takim, jakim go dzisiaj odbieramy.“[45]

Drażliwość i aktualność problematyki podzielonej pamięci uwidoczniła się przed uroczystościami 9. maja 2005 roku w Moskwie. Doświadczenia sowieckiego panowania w krajach bałtyckich oraz hegemonia Związku Radzieckiego wobec innych krajów bloku wschodniego pozostawiły do dzisiaj swoje mentalne ślady i są nadal elementem konstytuującym zbiorową historyczną świadomości tych krajów. Z drugiej strony w Europie Zachodniej rzadko spotykamy pogłębioną wiedzę, o sytuacji ludzi w krajach bałtyckich, brak znajomości auto- i heterostereotypów Łotyszy, Estończyków, Łotyszy, Litwinów i Polaków napiętnowanych przez określone doświadczenia historyczne. Niektóre współczesne polityczne wypowiedzi i sposoby postępowania dają się wytłumaczyć jedynie na podstawie konkretnych historycznych doświadczeń. [46]

Jakie są metody i drogi, aby dzisiaj złagodzić nadal skonfliktowane światy pamięci „starej“ i „nowej“ Europy? Odpowiedź na to pytanie wymaga ostrożności, gdyż mamy tu często do czynienia z zachodnimi deficytami w postrzeganiu, spowodowanymi z jednej strony inną socjalizację spod znaku społecznej amerykanizacji i w związku z tym z innymi doświadczeniami pokoleniowymi, z drugiej zaś ze skutkami ideologicznie propagowanej i praktykowanej polityki izolacjonizmu „bloku wschodniego“. Kolejnym utrudnienie jest to, że deficytu tego nie można już nadrobić, bo w Europie wschodniej chodziło o dyktaturę, która w latach 1989-1990 implodowała i tym samym nie można jej już bezpośrednio doświadczyć, ale żyje nadal w biografiach, wspomnieniach i urazach milionów ludzi.

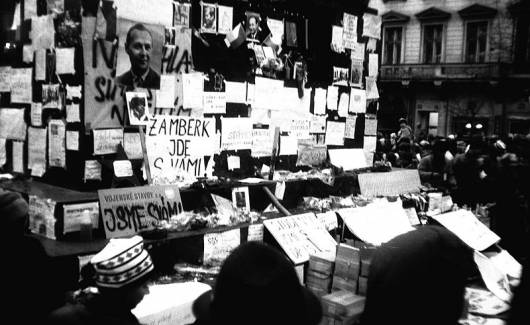

Działalność obrońców praw obywatelskich i opozycjonistów w Europie Środkowowschodniej dopomina się o włączenie jej do europejskiej historii wolności, jako przykład urzeczywistniania społeczeństwa obywatelskiego. Gdyż to właśnie oni, doprowadzili nie tylko do rozpadu państwowego socjalizmu, ale również do przezwyciężenia porządku jałtańskiego i wsparli ideę jednej Europy. Wolfgang Eichwede określił ich jako spadkobiercy, ponieważ swoja odwagą, wiarą w społeczeństwo i siłą własnego przykładu, stworzyli w 1989 roku podwaliny społeczeństwa obywatelskiego.[47]

*

Zadaniem powstałej z inicjatywy Polski, Niemiec, Węgier i Słowacji w 2005 roku „Europejskiej Sieci Pamięć i Solidarność“ jest przyczynie się do zbliżenia różnych światów pamięci. Punktem wyjścia Sieci była tak zwana „Deklaracja Gdańska“ z 29. października 2005 roku podpisana przez ówczesnych prezydentów Aleksandra Kwaśniewskiego i Johannesa Raua. „Deklaracja Gdańska” była reakcją na prowadzoną częściowo w kontrowersyjny sposób, dyskusję w ramach i między społeczeństwami obu krajów, problematyce wypędzeń w XX wieku. W Deklaracji obaj prezydenci zasugerowali „Europejczycy winni razem na nowo ocenić i udokumentować wszystkie przypadki wysiedleń, ucieczek i wypędzeń, które miały miejsce w XX wieku”. [48]

W lutym 2005 roku ministrowie kultury Polski, Niemiec, Węgier i Słowacji podpisali wspólną deklarację o zamiarze utworzenia Europejskiej Sieci. W deklaracji uwzględniono różne potrzeby w zakresie pamięci poszczególnych krajów. Czytamy: ”Przedmiotem działalności sieci będzie analiza, dokumentowanie i upowszechnianie wiedzy o historii XX wieku; wieku wojen, totalitarnych dyktatur i cierpień ludności cywilnej – ofiar wojen, ucisku, podbojów i przymusowych wysiedleń oraz represji nacjonalistycznych, rasowych i motywowanych ideologicznie“ [49]

W szeroki sposób sformułowany zakres działalności Sieci jest wyrazem dążenia do opartej na dialogu kultury pamięci, dając wystarczającą przestrzeń dla projektów naukowych oraz popularnonaukowych nie zamykając ją na przyjęcie innych zainteresowanych krajów. Kolejność wymienionych zadań Sieci jest zgodna z wagą tych zdarzeń w historii, gdzie przymusowe migracje stanowią jeden z elementów historii XX wieku i konieczne jest włączenie ich w kontekst dynamiki działań wojennych. Przymusowe migracje nie są najważniejszymi i najbardziej dramatycznymi wydarzeniami, jakie przeżyli środkowowschodni Europejczycy. To, co odcisnęło się w najbardziej dramatyczny i bolesny sposób na europejskiej, a w szczególności, na środkowowschodnio-europejskiej historii XX wieku to doświadczenia dwóch totalitaryzmów: nazizmu i komunizmu z piętnem Auschwitz i gułagu. Elementem wspólnym wyrażonym w opisie zadań jest niepodzielna empatia dla wszystkich ofiar historii.[50]

We wrześniu 2005 roku Rada Fundacji pod przewodnictwem Andrzeja Przewoźnika, ówczesnego sekretarza Rady Ochrony Pamięci Walk i Męczeństwa, przyjęła statut Fundacji „Europejskiej Sieci Pamięć i Solidarność“. Jako Fundatora udało się pozyskać znamienitego artystę, teatrologa i byłego więźnia Auschwitz Józefa Szajnę. Jednocześnie w Warszawie ukonstytuowała się Rada Fundacji, której członkiem ze strony niemieckiej jest Matthias Weber z Federalnego Instytutu ds. Kultury i Historii Niemców w Europie Wschodniej. Deklaracja z lutego 2005 roku o utworzeniu Europejskiej Sieci spotkała się z szerokim medialnym odzewem, oraz pozytywnym odbiorem instytucji i organizacji oświatowych zajmujących się pamięcią, które wyrażały swoją gotowość do współpracy.[51]

Zadaniem Sieci jest również przyczynianie się do przezwyciężania skutków trwającego przez dziesięciolecia podziału Europy, tak aby wymieniając historyczne doświadczenia wojen, dyktatur i przymusowych migracji móc spojrzeć i poznać losy innych narodów. Do celów Sieci należy również połączenie już istniejących inicjatyw i instytucji na rzecz wspierania dialogowej kultury pamięci oraz kulturowego pogłębienia Unii Europejskiej.

Jakie są metody i tematy działalności mogące stanowić o profilu Sieci?

Po pierwsze, w europejskim krajobrazie pamięci istnieje szczególny okres, na który skierowana jest tak indywidualna jak i narodowa pamięć. Jest nim II wojna światowa. Była to znacząca cezura, która przyniosła zniszczenia, wypędzenia, nędzę i ucisk, ale również wyzwolenie i nowy początek. Konsekwencją wojny było rozerwanie Niemiec i Europy na dwie części, a w ślad za tym losy i życiorysy ludzi na Wschodzie i Zachodzie kształtowały się przez długi czas odmiennie.

Sieć ma zająć się w kontekście historycznym tak tematem ucieczek i wypędzeń, zainteresowanie którym artykułowane jest od kilku lat w Niemczech, jak i tematami okupacji nazistów w Europie Środkowowschodniej, które dla strony polskiej jest szczególnie istotne. Tu Europejska Sieć może rozpocząć swoją działalność, włączając perspektywę „tego drugiego”, próbując zrozumieć wrażliwe dla sąsiada punkty i włączyć je do własnego obrazu historii i tym samym połączyć narrację historyczną narodów europejskich.

Po drugie, temat wschodnich doświadczeń wraz z pamięcią o komunizmie przeciwstawiając ją pamięci o nazizmie stanowi centralny temat europejskiej historii, choć dopiero w niewielu publikacjach zajął miejsce głównej osi narracji. Wskazówką mogą być prace François Fureta, Marka Mazowera i Tony'ego Judta.[52] Ci trzej historycy pokazali kompetentnie i trafnie, jak długi cień II wojna światowa rzuciła na całą powojenną Europę, naznaczyła polityczne losy i wysiłki integracyjne na Wschodzie i Zachodzie oraz skodyfikowała - również ponad granicami - kulturowe wzorce.

Po trzecie, porównanie sytuacji w państwach realnego socjalizmu mogłoby wnieść informacje o tym, jak poszczególne rządzące partie usiłowały godzić ze sobą wyłączność na przywództwo i kształtowanie rzeczywistości z koniecznością modernizacji gospodarki, dążeniem społeczeństw do dobrobytu i demokratyzacji. W ten sposób można by było scharakteryzować mechanizmy i formy integracji oraz ponadnarodowe kulturowe wpływy na socjalistyczne kraje Europy Wschodniej. Tego rodzaju analiza, podejmowana dotychczas w bardzo ograniczonym zakresie,[53] mogłaby dokładniej naświetlić nie tylko powody rozpadu i pokojowego końca „bloku wschodniego“, ale również dziesięciolecia jego trwania i stabilności.

Równie interesującym jest porównanie oporu i opozycji w krajach byłego „bloku wschodniego“. Jakimi wzorcami tradycji oporu i doświadczeniami z rządzącymi partiami dysponowały grupy opozycyjne w poszczególnych krajach? Jakie społeczne oparcie posiadali opozycjoniści? Te i inne pytania - mimo trudności uogólniającego zdefiniowania pojęć „dysydent” i „opozycja” - czynią szczególnie cennym porównanie ruchów społecznych w sensie heurystycznym, ale również jako katalizatorów dla demokratycznych reform i jako aktorów rewolucji 1989 roku.[54]

Po czwarte, historia zintegrowanego ew. zdezintegrowanego Wschodu nadaje się do zbadania historii stosunków z Zachodem. Byłoby to ważne na przykład ze względu na komunikację z Zachodem, tę w formie prywatnej odbieranej często jako atrakcyjna wymiana poglądów oraz tę szczebla oficjalno-państwowego z licznymi zakłóceniami. Z drugiej strony należałoby zapytać, czy zachodnioeuropejska integracja nie była odpowiedzią na polityczne i ekonomiczne wyzwanie „bloku wschodniego” z początkowo wysoką stopą wzrostu.[55]

Integracja była wprowadzana w krajach socjalistycznych „odgórnie“, podobnie jak w początkowych latach na zachodzie Europy, jednak od lat 70. zdecydowanie różniła się w swoim społeczno-politycznym oddziaływaniu i szerokiej akceptacji wśród Europejczyków z Zachodu. Ideowy fundament wschodnioeuropejskiej integracji był stale bardzo kruchy. Rzekomy socjalistyczny system wartości zbyt mało odróżniał się od zachodniego, ponieważ częściowo posiadał te same historyczne korzenie lub cele, jak dążenie do gospodarczego dobrobytu. Będący faktycznie systemem ucisku socrealizm był aktywnie utrzymywany i pozytywnie interpretowany przez określone grupy, które stanowiły mniejszość społeczeństwa. Przy całej narodowej specyfice, zwłaszcza w stosunku do przemocy państwa, większość ludności Europy Wschodniej raczej znosiła niż podtrzymywała system represji.[56]

Rozpoczęta w latach 60. na Zachodzie zmiana wartości w duchu postmodernistycznym ukazała różnice między Wschodem a Zachodem, podnosząc – chcąc nie chcąc – atrakcyjność coraz bardziej wyimaginowanego Zachodu. Społeczna mobilność i zdolność do innowacji stały się znakami firmowymi na Zachodzie, podobnie jak: ekologia, feminizm, kończące się surowce, imigracja i wielokulturowe społeczeństwo; tematy, które były prawie nieobecne na Wschodzie.[57]

Zajmując się wspomnieniami i pamięcią w europejskim XX wieku pomocna mogłaby okazać się idea „lieux de mémoire“ (miejsc pamięci). Zastosowana przez Pierre Nora we Francji metoda zebrania, kategoryzacji, a tym samym ustanowienia kanonu „lieux de mémoire“ znalazło już naśladowców oraz poddana została modyfikacjom wobec uwarunkowań w innych krajach, co już samo w sobie stanowi godną odnotowania europeizację.[58] Projekty dotyczące materialnych i niematerialnych miejsc pamięci pozwalają na wprowadzenie do aktualnej rzeczywistości kulturowych czynników wspomnień które pozwalają ze zmian form pamięci na przestrzeń dłuższych okresów tematem dyskusji. W ostatnich latach również w Niemczech tematyka miejsc pamięci spotkała się ze znacznym zainteresowaniem nauki.[59] Są także oznaki, że problematyką miejsc pamięci zajmują się coraz intensywniej naukowcy z Europy Środkowowschodniej. [60]

W wielu europejskich krajach widoczne są, podyktowane narodowymi paradygmatami, starania na rzecz polityki historycznej i oficjalnej kultury pamięci.[61] Nie należy jednak z góry traktować tego podejrzliwie. Należy je natomiast w ramach projektów Sieci uwzględnić jako różne rodzaje narracji w naukowej dyskusji. Przy tym nie może chodzić o europejskie ujednolicenie narodowych ram, w których konstytuuje się pamięć o wojnie i przemocy. Zadaniem raczej będzie spostrzeżenie różnych sposobów zaszeregowywania winy i odpowiedzialności jako istniejące linie podziałów w europejskiej przestrzeni pamięci. O nich musimy również w ramach Sieci stale pamiętać, choćby po to, aby móc wytrzymać własną przeszłość. Reinhart Koselleck powiedział dobitnie: „Nie możemy zachować naszej pamięci bez wspominania o tych nie do pokonania pęknięć. Inaczej bylibyśmy nieuczciwi w stosunku do samych siebie.“[62] Gdyby Sieciudało się te pęknięcia w europejskim krajobrazie pamięci odsłonić i przezwyciężyć, w taki sposób, że będziemy pamiętali o czułych punktach sąsiadów i przejmiemy perspektywę patrzenia „innych”, to uzyskamy więcej niż mogli mieć nadzieję założyciele Europejskiej Sieci Pamięć i Solidarność.

dr Burkhard Olschowsky (ur. 1969 w Berlinie) studiował historię i historię Europy wschodniej w Getyndze, Warszawie i Berlinie. W 2002 r. obronił doktorat na Uniwersytecie Humboldta w Berlinie. W latach 2003-2005 pracował jako wykładowca kontraktowy z dziedziny historii współczesnej i polityki na Uniwersytecie Humboldta. W latach 2004-2005 pracował w Federalnym Ministerstwie Transportu, Budownictwa i Mieszkalnictwa. Od maja 2005 pracownik naukowy w Federalnym Instytucie ds. Kultury i Historii Niemców w Europie Środkowej i Wschodniej. Od 2010 pracownik naukowy w Sekretariacie Europejskiej Sieci Pamięć i Solidarność.

1 Heinrich August Winkler: Vom linken zum rechten Nationalismus: Der deutsche Liberalismus in der Krise von 1878/79. In: Ders.: Liberalismus und Antiliberalismus. Göttingen 1979, S. 36–51.

2 Hagen Schulze: Staat und Nation in der europäischen Geschichte. München 1999, S. 320.

3 Ute Frevert: Eurovisionen. Ansichten guter Europäer im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert (= Europäische Geschichte). Frankfurt a. M. 2003, S. 148f.

4 Vgl. Gregor Thum: „Europa“ im Ostblock. Weiße Flecken in der Geschichte der europäischen Integration. In: Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History, Online-Ausgabe, 1 (2004), H. 3, S.1.; Peter Bender: Das Ende des ideologischen Zeitalters. Die Europäisierung Europas. Berlin 1981; Karl Schlögel: Die Mitte liegt ostwärts. Die Deutschen, der verlorene Osten und Mitteleuropa. Berlin 1986.

5 Ernst Friedländer: Wie Europa begann. 2. Aufl. Köln 1968, S. 50.

6 Uczestnikami z zachodniej Europy byli między innymi Pablo Picasso, Hans Scharoun, Max Frisch, Max Pechstein, Paul Éluard, Fernand Léger, Irena Joliot-Curie, Hans Mayer.

7 Gregor Thum: „Europa“ im Ostblock (Anm. 4), S. 3; Hans Mayer: Ein Deutscher auf Widerruf. Erinnerungen. Bd. 1. Frankfurt a. M. 1988, S. 397–411.

8 Jan Čulik: Tschechisches literarisches Leben im Exil 1971–1989. In: Ludwig Richter, Heinrich Olschowsky (Hg.): Im Dissens zur Macht. Samizdat und Exilliteratur in den Ländern Ostmittel- und Südosteuropas (= Forschungen zur Geschichte und Kultur des östlichen Mitteleuropas). Berlin 1995, S. 69–84, hier S. 70.

9 Juliane Brandt: Ungarische Exilliteratur – Ungarische Literatur im Westen. In: Richter, Olschowsky (Hg.): Im Dissens zur Macht (Anm. 8), S. 169–190, hier S. 173, 175.

10 Andrzej Stanisław Kowalczyk: Giedroyc i „Kultura“. Wrocław 1999; Krzysztof Kopczyński: Przed przystankien Niepodległość. Paryska „Kultura“ i kraj w latach 1980–1989 Warszawa 1990.

11 Milan Kundera: Un Occident kidnappé – oder Die Tragödie Zentraleuropas. In: Kommune 7 (1984), S. 43–52, hier S. 44.

12 György Konrad: Antipolitik. Frankfurt a. M. 1985, S. 76ff., 145ff.

13 Zu den tschechoslowakischen, ungarischen und polnischen Stimmen siehe Hans-Peter Burmeister, Frank Boldt, György Mészáros (Hg.): Mitteleuropa. Traum oder Trauma? Bremen 1988; Krystyna Rogaczewska: Niemcy w myśli politycznej polskiej opozycji w latach 1976–1989 [Deutschland im politischen Denken der polnischen Opposition in den Jahren 1976-1989]. Wrocław 1998, S. 125, 141.

14 Vgl. Hermann Rudolph: Ein Stellvertreterkrieg am falschen Platz. Zur Mitteleuropa-Diskussion in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. In: Hans Ester, Hans Hecker, Erika Poettgens (Hg.): Deutschland, aber wo liegt es? Deutschland und Mitteleuropa (= Amsterdam Studies of Cultural Identity 3). Amsterdam, Atlanta 1993, S. 323–334; Peter Bender: Die Notgemeinschaft der Teilungsopfer. In: Ebd., S. 335–350.

15 Czesław Miłosz: Verführtes Denken. Frankfurt a. M. 1980, S. 8.

16 Heinrich Olschowsky: Emigrantenschicksal und literarische Strategie. Überlegungen zu Czesław Miłosz. In: Richter, Olschowsky (Hg.): Im Dissens zur Macht (Anm. 8), S. 55–68, hier S. 56ff; Janusz Reiter: Geteilte Erinnerung im Vereinten Europa. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 7.5.2005.

17 Reinhart Koselleck: Gebrochene Erinnerung? Deutsche und polnische Vergangenheiten. In: Deutsche Akademie für Sprache und Dichtung, Jahrbuch 2000, S. 19–32, hier S. 20f.

18 Hans Günter Hockerts: Zugänge zur Zeitgeschichte: Primärerfahrung, Erinnerungskultur, Geschichtswissenschaft. In: Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, B 28/2001, S. 15–30. Debata Goldhagena uwypukliła, jak bardzo nauka i społeczeństwo medialne mogą znaleźć się w konflikcie. Im bardziej historycy znają się na temacie, tym mocniejsza jest z reguły krytyka. Nie umniejsza to jednak niezwykłego medialnego sukcesu amerykańskiego politologa. Wręcz przeciwnie przydaje tematycznie niezwykle podobnej – aczkolwiek znacznie lepszej naukowo - książce Christophera Browninga niezwykłego znaczenia dla debaty medialnej. Oznacza to brak kampanii PR i uproszczonych tez, a także oglądania się na wskaźniki oglądalności. Ruth Bettina Birn, Volker Riess: Das Goldhagen-Phänomen oder: fünfzig Jahre danach. In: Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht 49 (1998), S. 80–95; Christopher Browning: Ganz normale Männer. Das Reserve-Polizeibataillon 101 und die „Endlösung“ in Polen. Reinbek 1993.

19 Hans Günter Hockerts: Zugänge zur Zeitgeschichte: Primärerfahrung, Erinnerungskultur, Geschichtswissenschaft. In: Konrad Jarausch, Martin Sabrow (Hg.): Verletztes Gedächtnis. Erinnerungskultur und Zeitgeschichte im Konflikt. Frankfurt a. M., New York 2002, S. 39–71, hier S. 41.

20 Vgl. Michael Mann: The Dark Side of Democracy. Explaining Ethnic Cleansing. Cambridge 2005, S. 34ff.; vgl. Philipp Ther: A Century of Forced Migration: The Origins und Consequences of „Ethnic Cleansing“. In: Ders., Ana Siljak (Hg.): Redrawing Nations. Ethnic Cleansing in East-Central Europe 1944–1948 (= Harvard Cold War Studies Book Series 1). Lanham 2001, S. 43–74; Norman Naimark: Flammender Haß: ethnische Säuberung im 20. Jahrhundert. München 2004, S. 9ff., 231ff.

21 Vgl. Michael G. Esch: „Gesunde Verhältnisse“. Deutsche und polnische Bevölkerungspolitik in Ostmitteleuropa 1939–1950 (= Materialien und Studien zur Ostmitteleuropa-Forschung 2). Marburg 1998, S. 128ff, S. 176ff.

22 Jörg Baberowski: Ordnung durch Terror. Stalinismus im sowjetischen Vielvölkerreich. In: Isabel Heinemann, Patrick Wagner (Hg.): Wissenschaft – Planung – Vertreibung. Neuordnungskonzepte und Umsiedlungspolitik im 20. Jahrhundert. Stuttgart 2006, S. 145-172, hier S. 146; vgl. Eric D. Weitz: A Century of Genocide. Utopias of Race and Nation. Princeton 2003, S. 8–15.

23 Vejas Gabriel Liulevicius: Kriegsland im Osten, Eroberung, Kolonisierung und Militärherrschaft im Ersten Weltkrieg. Hamburg 2002, S. 275ff.

24 Baberowski: Ordnung durch Terror (Anm. 22), S. 147.

25 Karl Schlögel: Wie europäische Erinnerung an Umsiedlung und Vertreibung aussehen könnte. In: Anja Kruke (Hg.): Zwangsmigration und Vertreibung – Europa im 20. Jahrhundert. Bonn 2006, S. 49–68, hier S. 55.

26 Holm Sundhaussen: Bevölkerungsverschiebungen in Südosteuropa seit der Nationalstaatswerdung (19./20. Jahrhundert). In: Comparativ 6 (1996), S. 25–40, hier S. 38.

27 Philipp Ther: Ein Jahrhundert der Vertreibung. Die Ursachen von ethnischen Säuberungen im 20. Jahrhundert. In: Ralph Melville, Claus Scharf (Hg.): Zwangsmigrationen in Europa 1938–1945. Mainz 2007 (im Druck).

28 Tomasz Falęcki: Niemieckie szkolnictwo mniejszościowe na Górnym Śląsku w latach 1922–1939 [Das Schulwesen der deutschen Minderheit in Oberschlesien in den Jahren 1922–1939]. Katowice 1970, S. 67f.

29 Wacław Długoborski: Das Problem des Vergleichs von Nationalsozialismus und Stalinismus. In: Dittmar Dahlmann, Gerhard Hirschfeld (Hg.): Lager, Zwangsarbeit, Vertreibung und Deportation. Dimensionen der Massenverbrechen in der Sowjetunion und in Deutschland 1933 bis 1945 (= Schriften der Bibliothek für Zeitgeschichte 10). Essen 1999, S. 19–28.

30 PVAP: Polnische Vereinigte Arbeiterpartei.

31 Gesine Schwan: Die Last zweier Vergangenheiten. In: Thomas Brose (Hg.): Deutsches Neuland. Beiträge aus Religion und Gesellschaft. Leipzig 1996, S. 24–33, hier S. 31.

32 Siehe den aussagekräftigen Querschnitt an vergleichenden Arbeiten über das „Dritte Reich“ und die DDR. Günter Heydemann, Detlef Schmiechen-Ackermann: Zur Theorie und Methodologie vergleichender Diktaturforschung. In: Günter Heydemann, Heinrich Oberreuter (Hg.): Diktaturen in Deutschland – Vergleichsaspekte (= Schriftenreihe der Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung 398). Bonn 2003, S. 9–55, hier S. 14.

33 „Pomówmy o dylematach“, z Tadeuszem Mazowieckim rozmawia ks. Adam Boniecki. In: Tygodnik Powszechny, 22.4.2007, S. 12; Piotr Grzelak: Wojna o lustrację [Der Krieg um die Lustration]. Warszawa 2005, S. 17–25.

34 Bronisław Wildstein: Der Antikommunismus nach dem Kommunismus. In: Paweł Śpiewak (Hg.): Anti-Totalitarismus. Eine polnische Debatte (= Denken und Wissen. Eine Polnische Bibliothek). Frankfurt a. M. 2003, S. 527–542.

35 Rudolf Jaworski: Kollektives Erinnern und nationale Identität. Deutsche und polnische Gedächtniskulturen seit Ende des Zweiten Weltkrieges. In: Ewa Kobylińska, Andreas Lawaty (Hg.): Erinnern, Vergessen, Verdrängen. Polnische und deutsche Erfahrungen (= Veröffentlichungen des Deutschen Polen-Instituts Darmstadt 11). Wiesbaden 1998, S. 33–52, hier S. 48.

36 Vgl. Tomasz Szarota: Mord in Jedwabne – Dokumente, Publikationen und Interpretationen aus den Jahren 1941–2000. Ein Kalendarium. In: Edmund Dmitrów, Paweł Machcewicz, Tomasz Szarota (Hg.): Der Beginn der Vernichtung. Zum Mord an den Juden in Jedwabne und Umgebung im Sommer 1941 (= Veröffentlichungen der Deutsch-Polnischen Gesellschaft Bundesverband e.V. 4). Osnabrück 2004, S. 209-252; Halina Bortnowska: Wenn der Nachbar keinen Namen hat. In: Transodra 23 (2001), S. 122–124.

37 Rede Sandra Kalnietes zur Eröffnung der Leipziger Buchmesse, 24.3.2004.

38 Salomon Korn: Vorsicht vor Antisemitismus aus Osteuropa. In: Leipziger Volkszeitung, 26.3.2004.

39 Ijoma Mangold: Salomon Korns Protest. Der Historikerstreit lässt grüßen. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung, 25.3.2004; Matthias Arning: Rückkehr des Totalitären. In: Frankfurter Rundschau, 15.4.2004.

40 Sandra Kalniete: Mit Ballschuhen im sibirischen Schnee. Die Geschichte meiner Familie. München 2005.

41 Positive Rezensionen unter anderem von Hubertus Knabe: Ballschuhe im Schnee. In: Tagesspiegel, 1.8.2005; Christian Esch: Nachgeholte Tränen. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung, 21.3.2005; Anita Klüger: Ratten in Brennnesselsud. In: tazMagazin, 21.5.2005; negative Rezension von Michael Wolffsohn: Keine Gesellen nirgends. In: Die Welt, 16.4.2005.

42 Z niemieckim wojskiem kolaborowały przede wszystkim dowodzone przez Viktora Arajsa paramilitarne ugrupowania grupujące ok. 200 osób, które od lata 1941 r. brały aktywny udział w mordowaniu łotewskich Żydów. Członkowie oddziałów Arajsa byli postrzegani przez Łotyszy niezwykle negatywnie. Kathrin Reichelt: Zwei Beispiele der Judenverfolgung in Lettland 1941–1944. In: Joachim Tauber (Hg.), „Kollaboration“ in Nordosteuropa. Erscheinungsformen und Deutungen im 20. Jahrhundert (Veröffentlichungen des Nordost-Instituts 1). Wiesbaden 2006, S. 77–87, hier S. 80f.

43 Basil Kerski: Ungleiche Opfer. In: Kafka. Zeitschrift für Mitteleuropa, H. 14 (2004). S. 34–43; Jasper von Altenbockum: Der lange Schatten. Lettland und die „Gleichsetzung“ von Stalinismus und Nationalsozialismus. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 3.4.2004.

44 Vgl. Andrzej Paczkowski: Gedächtniswelten. Das „alte“ und das „neue“ Europa. In: Bernd Kauffmann, Basil Kerski (Hg.): Antisemitismus und Erinnerungskulturen im postkommunistischen Europa (= Veröffentlichtungen der Deutsch-Polnischen Gesellschaft Bundesverband e.V. 10). Osnabrück 2006, S. 135–145.

45 Anne Applebaum: Der GULAG. Berlin 2003, S. 609.

46 Heinrich August Winkler: Erinnerungswelten im Widerstreit. Europas langer Weg zu einem gemeinsamen Bild vom Jahrhundert der Extreme. In: Kauffmann, Kerski (Hg.): Antisemitismus und Erinnerungskulturen (Anm. 43), S. 105–116, hier S. 114; vgl. Roland Freudenstein: Warum die EU gegenüber Russland mit einer Stimme sprechen muss. In: Dialog, H. 77–78 (2007), S. 68–70; Lilija Ševcova: Garantiert ohne Garantie. Rußland unter Putin. In: Osteuropa, 3 (2006), S. 3–18, hier 13 ff.

47 Wolfgang Eichwede: Kinder der Aufklärung. In: Kafka. Zeitschrift für Ostmitteleuropa 3 (2001), S. 8–13; vgl. Jerzy Giedroycs Kultura und die Krise der europäischen Identität. In: Łukasz Galecki, Basil Kerski (Hg.): Die polnische Emigration und Europa 1945–1990. Eine Bilanz des politischen Denkens und der Literatur Polens im Exil. Osnabrück 2000, S. 73–94, hier S. 91ff.

48 www.bundeskanzlerin.de/bk/Redaktion/Binaer/2005/12/2005-12-02-danziger-erklaerung-pdf,property=blob.pdf

49 www.markusmeckel.de/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=231-

50 Paweł Machcewicz: Ein Netzwerk aus polnischer Sicht. In: Kruke (Hg.): Zwangsmigrationen und Vertreibung (Anm. 25), S. 147–150, hier S.148f.

51 http://www.polskiejutro.com/art/a.php?p=144-145okiem.

52 François Furet: Das Ende der Illusion. Der Kommunismus im 20. Jahrhundert. München 1996; Mark Mazower: Der dunkle Kontinent: Europa im 20. Jahrhundert. Berlin 2000; Tony Judt: Geschichte Europas von 1945 bis zur Gegenwart. München 2006.

53 Zur wirtschaftlichen Integration: Ralf Ahrens: Gegenseitige Wirtschaftshilfe? Die DDR im RGW. Strukturen und handelspolitische Strategien 1963–1976 (= Schriftenreihe des Hannah-Arendt-Institutes für Totalitarismusforschung 15). Köln u. a. 2000; sozialgeschichtliche Überblicksdarstellung: Mark Pittaway: Eastern Europe 1939–2000. London 2004; alltagsgeschichtlich: David Crowley, Susan E. Reid (Hg.): Socialist Spaces. Sites of Everyday Life in the Eastern Bloc. Berg 2002; eine sehr aussagekräftige Fallstudie über die weitreichende Hochschul- und Kaderpolitik: John Connelly: Captive University. The Sovietization of East German, Czech and Polish Higher Education, 1945–1956. Chapel Hill u. a. 2000.

54 Helmut Fehr: Unabhängige Öffentlichkeit und soziale Bewegungen. Fallstudien über Bürgerbewegungen in Polen und der DDR. Opladen 1996; Detlef Pollack, Jan Wielgohs (Hg.): Dissent and Opposition in Communist Eastern Europe. Origins of Civil Society and Democratic Transition. Aldershot 2004; Manfred Agethen, Günter Buchstab (Hg.): Oppositions- und Freiheitsbewegungen im früheren Ostblock. Freiburg 2003.

55 Jürgen Kocka: Der Blick über den Tellerrand fehlt. DDR-Forschung – weitgehend isoliert und zumeist um sich selbst kreisend. In: Deutschland Archiv 36 (2003), S. 764–769.

56 Wolfgang Schmale: Wie europäisch ist Ostmitteleuropa?. In: Themenportal Europäische Geschichte (2006), S. 7; Helena Flam: Mosaic of Fear. Poland and East Germany before 1989. New York 1998.

57 Andreas Rödder: Wertewandel und Postmoderne. Gesellschaft und Kultur in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 1965–1990 (= Kleine Reihe / Stiftung Bundespräsident-Theodor-Heuss-Haus 12). Stuttgart 2004; Włodzimierz Borodziej: Der Standort des Historikers und die Herausforderung der europäischen Geschichte. In: Gerald Stourzh (Hg.): Annäherungen an eine europäische Geschichtsschreibung (= Archiv für österreichische Geschichte 137). Wien 2002, S. 105–118, hier S. 116.

58 Pierre Nora (Hg.): Les lieux de mémoire. 7 Bde. Paris 1984–1992; Mario Isnenghi (Hg.): I luoghi della memoria. 3 Bde. Rom, Bari 1987–1997; Moritz Csáky (Hg.): Orte des Gedächtnisses. Wien 2000; Pim den Boer, Willem Frijhoff (Hg.): Lieux de mémoire et identités nationales. Amsterdam 1993.

59 Etienne François: Eine Geschichte der deutschen Erinnerungsorte: Warum? Wie? in: Alexandre Escudier (Hg.): Gedenken im Zwiespalt. Konfliktlinien europäischen Erinnerns (= Genshagener Gespräche 4). Göttingen 2001, S. 77–89; vgl. Etienne François, Hagen Schulze (Hg.): Deutsche Erinnerungsorte. Bde. 1–3. München 2001; Elke Stein-Hölkeskamp, Karl-Joachim Hölkeskamp (Hg.): Erinnerungsorte der Antike. Die römische Welt. München 2006.

60 Marcin Kula: Nośniki pamięci historycznej [Die Träger der historischen Erinnerung]. Warszawa 2002; Marek Czapliński, Hans-Joachim Hahn, Tobias Weger (Hg.): Schlesische Erinnerungsorte: Gedächtnis und Identität einer mitteleuropäischen Region. Görlitz 2005; Robert Traba: „Wschodniopruskość. Tożsamość narodowa i regionalna w kulturze politycznej Niemiec“ [Ostpreußentum. Nationale und regionale Identität in der politischen Kultur Deutschlands]. Poznań 2005.

61 Helmut König: Die Zukunft der Vergangenheit. Der Nationalsozialismus im politischen Bewußtsein der Bundesrepublik. Frankfurt a. M. 2003; Peter Oliver Loew: Zwillinge zwischen Endecja und Sanacja. Die neue polnische Rechtsregierung und ihre historischen Wurzeln. In: Osteuropa 11 (2005), S. 9–20; vgl. „Krise zwischen Ungarn und Slowaken eskaliert. Neue Ausfälle belasten die bilateralen Beziehungen“, Die Welt, 8.6.2006.

62 Reinhart Koselleck: Gebrochene Erinnerung? Deutsche und polnische Vergangenheiten. In: Deutsche Akademie für Sprache und Dichtung, Jahrbuch 2000. Göttingen 2000, S. 19–32, hier S. 29.